A podcast with C. Rangarajan, BR Ambedkar the economist, Fellowship deadlines

Ideas of India podcast, elite imitation in policy, Ambedkar Jayanti readings, and some fellowship deadlines

My conversation with Dr. C. Rangarajan

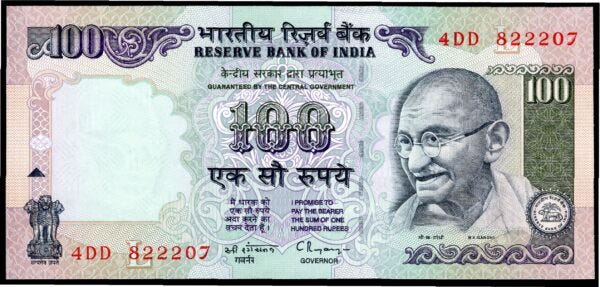

When asked why the Indian rupee didn’t end up a tin pot currency, I often credit its stability to Dr. C. Rangarajan, who was deputy governor of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) in 1991, and governor from 1992-97. His work alongside finance minister Dr. Manmohan Singh (‘92-96), and with Mr. P. Chidambaram (‘96-7), in the first few years after the crisis, was instrumental in bringing stability.

Typically, countries that face balance of payments and currency crises tend to stabilize briefly through IMF loans (that come with conditionalities), before regressing to their previous state. India had currency problems in the mid fifties. In 1966, India devalued the rupee and failed at implementing any economic reforms, discussed in the 1991 Project at Mercatus and covered in detail in this excellent essay by Prakhar Misra. But India never regressed with balance of payments and currency problems after 1991.

I had a chance to have a conversation with him on the Ideas of India podcast and ask him the same question: what did India do differently to ensure it didn’t have currency crises after 1991?

RANGARAJAN: This has been the experience of many countries which went to IMF, but the point is that we took reforms very seriously after we went to IMF. It is also proof of the fact that the reforms were not imposed. The reforms were our own making. We had decided that the time has come to move in a different direction, change from what we are doing earlier, and therefore, the additionality of the funds that came was a good thing.

They needed it at that time because the balance-of-payments crisis had to be overcome. Before we can initiate reforms, some degree of stability has to be established. Therefore, stability and reforms went together, and therefore we took the money from IMF and other international institutions and many others. The program that we wanted to initiate as a consequence of the crisis was something with which the IMF and other institutions were in agreement, and this was put down in the document of agreement. These are reforms which we thought were important from the point of view of the country, and this is what we want to do.

Therefore, very often people talk about the nature of conditionalities and so on. I would like to make a point: The conditionalities, if they want to call them that way, were conditionalities from their point of view. They were the reforms that we wanted to introduce at that particular time. Therefore, this is an important difference, perhaps, between the practices or between what happened in other countries or what happened to India also earlier.

Take one good example. We devalued the currency, but in the previous occasions when we devalued the currency, the steps that we took later on were essentially in the nature of controlling imports and so on. But whereas this time in 1991 when we devalued the currency, we went on to embrace, so to say, free trade and decided to become part of the global trade—in fact, reduce the tariff rates and remove the quantitative controls and so on. This is something contrary to what we used to do earlier after the decision to devalue the rupee. That will give you an idea of why the experiment this time, or results were far different from the earlier times.

This is an underappreciated point in policy formulation for developing countries. There is a tendency to "export" best practices from the developed world through IMF conditionalities, etc., or for the elites in developing countries to "import" practices that they observe from their peers in developed countries. However, neither approach is effective.

Exporting best practices through conditionalities may not have buy-in from the local elites, bureaucrats, and politicians who have to implement those policies at home. In the case of balance of payments crises, implementing bitter and electorally unpopular medicine, such as cutting government spending and bringing in fiscal discipline, can be challenging without buy-in. Such policies fail to take root.

Importing best practices can present a similar problem if the policies are not adapted to the local situation. In this paper, Alex Tabarrok and I argue that inappropriate imitation in India occurs because the Indian intelligentsia—the top people involved in politics, bureaucracy, universities, think tanks, foundations, and so forth—are closely connected with Anglo-American elites, sometimes even more closely than they are with the Indian populace. As a result, the Indian elite initiates and supports policies that appear to be normal but may have little relevance to the Indian population as a whole and may be wildly at odds with Indian state capacity. The result is first-world regulation that, at best, remains unimplemented, or worse, has a number of unintended consequence due to weak enforcement.

The incredible feat that the team of 1991 reformers pulled off was implementing best practices to deal with the currency crisis while transitioning the economy out of command and control, but in a completely homegrown way. They pursued some reforms gradually, such as reducing deficits and tariffs, while passing others with a single stroke, such as eliminating the license control system in trade and industry. Most of the reformers were career bureaucrats or technocrats who had built long-term relationships and trust within the Indian political system. Additionally, most of the reforms were based on the legwork done by expert committee reports over a decade prior to the 1991 reforms.

It wasn’t the Washington Consensus that saved the rupee, but its close cousin - the New Delhi consensus.

Dr. Rangarajan exemplifies the technocrat/civil servant who helped build that consensus. He earned his Ph.D. in economics at the University of Pennsylvania and after teaching at NYU and IIM Ahmedabad, he was the first economist to be laterally brought into the RBI as deputy governor in 1982. He served as a member of the Planning Commission in 1991 and as the governor of the Reserve Bank of India from 1992 to 1997. He has also served as the governor of the state of Andhra Pradesh, as chairman of the Twelfth Finance Commission, and as a member of parliament when he was appointed to Rajya Sabha. He chaired the Economic Advisory Council to the prime minister (Dr. Manmohan Singh) and currently serves as the chair of the Madras School of Economics. At 91 years old, he is still lecturing, writing, and is so busy that it took many weeks to schedule the podcast recording.

He just published his excellent memoir Forks in the Road: My Days at RBI and Beyond, detailing many decisions in his career, especially as central banker during the crisis in 1991 and the reforms that followed.

The entire conversation is excellent, and you can listen 👇 or read the full transcript.

ICYMI, this is the 77th episode of the Ideas of India podcast produced by the Mercatus Center. You can subscribe to the podcast on Apple, Spotify, Google, Overcast, Stitcher or the podcast app of your choice. We also produce fully linked transcripts available here.

Ambedkar Jayanti

It is B.R. Ambedkar's 132nd birth anniversary today. Celebrated worldwide as a Dalit icon, we often forget about Ambedkar, the economist who was trained at Columbia University under Edwin R.A. Seligman and at the London School of Economics with Edwin Cannan.

It's worth reading some of his works in economics for two reasons. First, they are quite different from the typical Marxist narrative around Ambedkar's thought. Both works are very much rooted in the neoclassical orthodoxy of the interwar years, and Ambedkar is writing about public finance, monetary policy, factor productivity, etc. Second, some of his writing on the Indian economy is still very relevant.

In The Evolution of Provincial Finance in British India (1923), Ambedkar criticized the highly centralized system of public finance in British India, which limited the ability of provincial governments to raise revenue and invest in development projects. Centralization also concentrated power in the hands of a few British elites. Since the rule of the East India Company, India has been plagued by a lack of state capacity and investment, and not much has changed after independence. India is still plagued by fiscal centripetalism, and many answers can be found in Ambedkar's work on increasing the revenue-raising capability of provincial and local governments, greater decentralization, and building the capacity of state finance commissions.

The his article Small Holdings In India And Their Remedies (1918) Ambedkar detailed the productivity problems of small land holdings, which have only become worse in modern-day India. Interestingly, many of the arguments Ambedkar made in this paper talked about the structural transformation required in the economy to modernize and mechanize agriculture, conducted with a small labor force, and a large and growing industrial sector to absorb people exiting agriculture. Ambedkar's view of the necessary exit from agriculture into industry is still underappreciated and unrecognized in Indian policy circles, which continues to romanticize agricultural and rural life.

[I]ndustrialization of India is the soundest remedy for the agricultural problems of India. The cumulative effects of industralization, namely, a lessening pressure and an increasing amount of capital and capital goods will forcibly create the economic necessity of enlarging the holding. Not only this, but industralization by destroying the premium on land will give rise to few occasions for its sub-division and fragmentation. Industrialization is a natural and powerful remedy and is to be preferred to such ill-conceived projects as we have considered above. By legislation we will get a sham economic holding at the cost of many social ills. But by industrialization a large economic holding will force itself upon us as a pure gain.

The Problem of the Rupee (1923), which Ambedkar submitted for his D.Sc. thesis at the LSE, criticizes the gold-exchange currency system of the colonial rupee. The system's goal was not to manage price stability for rupee holders by adjusting gold reserves. Instead, it maintained a fixed exchange rate between the Indian rupee and the British pound, resulting in chronic trade imbalances and a loss of gold reserves for India. Ambedkar suggested returning to a pure gold standard with a gold currency, which would be automatic and outside the manipulation of the colonial masters. Some of the arguments on large deficits, lack of prudential controls, and the impact of inflation on the poor are still extremely relevant.

Fellowship Application Deadlines!

My colleagues working on Academic and Student Programs at the Mercatus Centerhave created fantastic fellowship opportunities. I am an alumnus of this program and was a PhD. Fellow from 2008-13. The Lavioe and Buchanan Fellowship application deadlines are on April 15!

Mercatus Don Lavoie Fellowship - A competitive, virtual fellowship for advanced undergraduates, recent graduates considering graduate school, and early-stage graduate students.

● Award Total: $1,250

● Deadline: April 15, 2023

Mercatus James Buchanan Fellowship - A one-year, competitive fellowship awarded to scholars in any discipline who have recently graduated from their doctoral programs.

● Award Total: $15,000

● Deadline: April 15, 2023

What has really made a big difference to Indias BoP is the IT industry. In fact that is the entire story on why Indias bop is so much better. Last year after the oil prices spiked our current account deficit could have been in dire straits like our neighbors. The only difference was the massive net foreign exchange earnings of the IT industry. I guess the RBI and the govt can claim credit for that. They supported the industry in its infancy. But I don't know if much else they have done has moved the needle.