Altruism and Development - It's complicated.......

Effective altruism, air pollution in Delhi, Supreme Court of India, and trade off between legibility and complexity in evaluating philanthropic efforts.

As December rolls in, my inbox is filled with requests for donations, often from organizations I have given to in the past. This holiday season is also bittersweet because I cannot visit Delhi, where I was born and my parents still live, because of the air pollution and smog during the winter months. In Delhi, I find it hard to breathe, and usually lose my voice because of inflammation caused by particulate matter pollution. This year, I am under doctor’s orders to avoid travelling to Delhi in the winter; I’ve been struggling with respiratory problems from long Covid.

With air pollution dominating my thoughts and nudges for charitable giving in my inbox, my first instinct is to give to causes that help mitigate pollution in Delhi. But I am also aware of the literature on emotional giving or ineffective altruism. In their 2021 paper, Caviola, Schubert and Greene explain why both effective and ineffective causes may attract dollars. People often give emotionally to a cause that has personally impacted them in some way.

A US$100 donation can save a person in the developing world from trachoma, a disease that causes blindness. By contrast, it costs US$50,000 to train a guide dog to help a blind person in the developed world. This large difference in impact per dollar is not unusual. According to expert estimates, the most effective charities are often 100 times more effective than typical charities.

This paper resonated with me because I am exactly the sort of irrational dog lover likely to support the best training programs for guide dogs. These super dogs have my lifelong admiration. My Labrador retrievers can barely fetch a ball.

We all know air pollution is bad. But how bad? And compared to what?

As an alternative, I looked up the top charities recommended by GiveWell—the top two work on reducing Malaria deaths. Malaria kills between 600,000 and 700,000 each year. And GiveWell is considered one of the most credible evaluators in the philanthropic space. Should I be thinking less about air pollution in Delhi and more about malaria in Africa?

So, I thought it best to evaluate 1) my priors on air pollution, 2) whether air pollution mitigation in Delhi merits my dollars/rupees. And if Delhi air pollution merits intervention, then it would be good to 3) identify the reasons air pollution became such a big problem in Delhi (you would be surprised), which would lead to uncovering 4) how to mitigate the problem of air pollution so I can decide where to send my dollars. And since I got to #4, to understand 5) why people think that giving to malaria charities is “higher impact” than solving air pollution.

One simple Google search in I learned that globally air pollution kills 10 times the number of people killed by malaria. But the reason many researchers and experts feel that the “highest impact” comes from giving to malaria charities is because it is easier to quantify malaria deaths, and quantify malaria interventions by counting doses and nets, which lends itself well to evaluation and comparison. The top charities are listed as such not necessarily because the evaluators can objectively rank the most pressing problems or rank the institutions that have the highest impact on human well-being.

There are many reasons air pollution mitigation doesn’t make it to the top of these lists despite a ten times higher death toll. It cannot be avoided by distributing a $5 net. The costs and the benefits from air pollution in Delhi cannot be easily quantified. Nor can the benefits from the interventions to mitigate pollution be easily measured. Simply put, air pollution in Delhi is complex, while malaria death and malaria nets in Africa are legible. We can only evaluate impact of interventions and projects that are legible. And only studying complex phenomena narrowly can make them legible.

The very act of impact evaluation requires narrowing down the problem to make it legible and, in the process, other complex and unwieldy problems, that might be more pressing, will be left out. Impact evaluations only encompass the highest impact philanthropic efforts that we can measure and publish with confidence. Halfway into comparing air pollution and malaria, I had a renewed appreciation for James C. Scott’s ideas on the tradeoff between legibility and complexity. Air pollution mitigation institutions don’t make it to the top five of the GiveWell list because both the causes of air pollution and the interventions to mitigate pollution are complicated.

1. Is Air Pollution the Most Pressing Problem That Needs My Attention and Dollars?

YES!

Air pollution kills between 6.7 - 8.7 million people each year!

But how does air pollution compare with other leading causes of death? Still pretty bad ... it’s actually in the top three causes.

So, air pollution kills a lot of people. And even those who don’t prematurely die from pollution suffer—from worsened quality of life due to respiratory problems, losses in productivity, etc. It also adversely impacts individuals irrespective of their lifestyle. Short of moving cities or countries, it is not easily avoidable. And it hurts children the most.

For the rest of this post, I’ll use the 6.7 million estimate from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021, since it has the most recent data for Indian states.

2. How Bad is Air Pollution for Indians, Especially in Delhi?

Pretty bad! One in four people dying from air pollution live in India, where it is the leading cause of death. The total number of Indians dying prematurely due to air pollution is almost three times the total number of Africans dying from Malaria.

India has 17 percent of the global population but 25 percent of premature air pollution deaths.

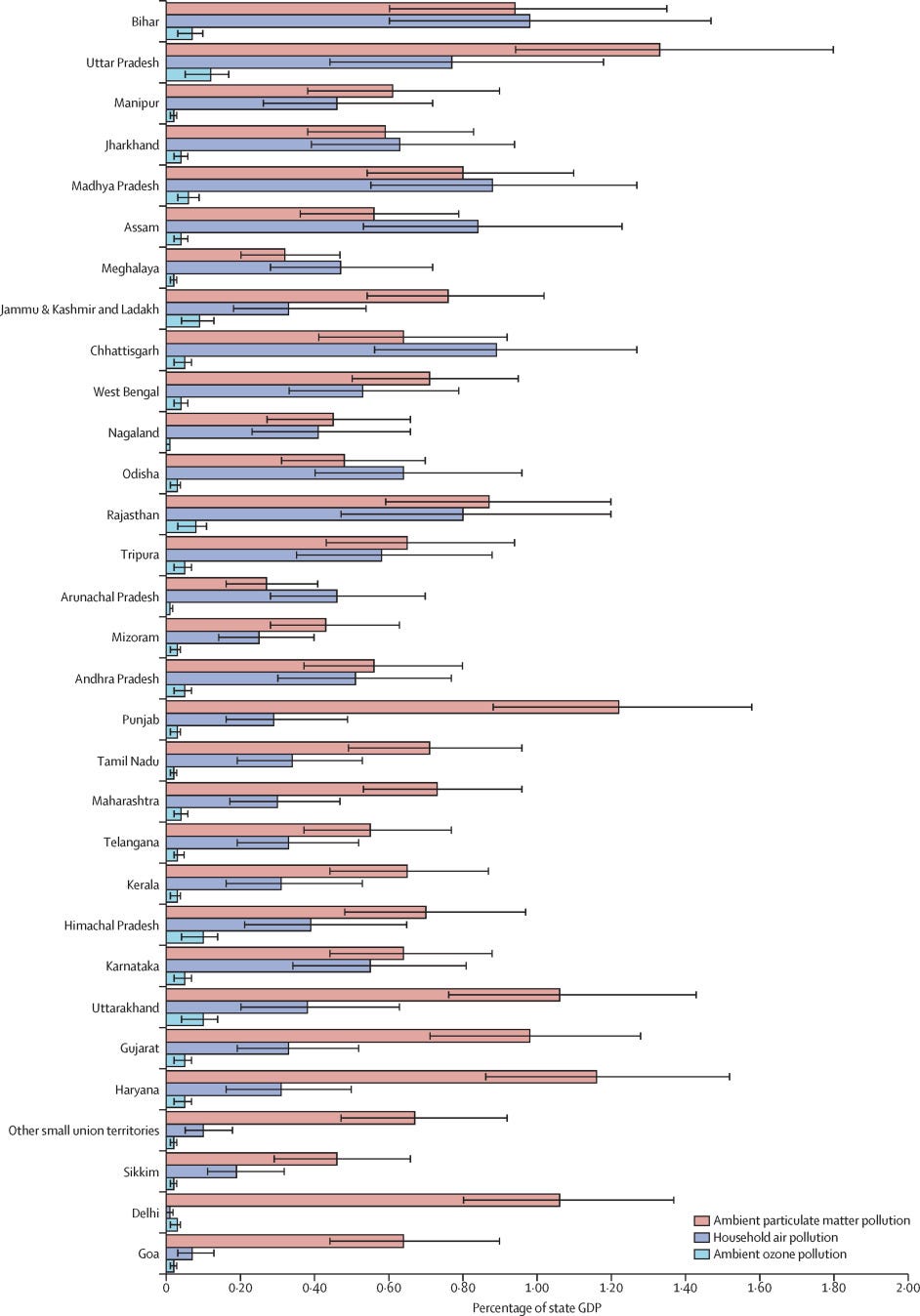

In their 2021 paper, “Health and economic impact of air pollution in the states of India: the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019,” Pandey et al. use the output-based approach to estimate the economic cost of premature deaths and morbidity attributable to air pollution in each state of India. The output-based approach equates the economic cost of premature mortality to the present value of lost income and measures the cost of morbidity by lost output.

They find that 1.67 million deaths were attributable to air pollution in India in 2019, accounting for 17.8% of the total deaths in the country. Lost output from premature deaths and morbidity attributable to air pollution accounted for economic losses of $28.8 billion and $8.0 billion, respectively, in 2019. This total loss of $36.8 billion was 1.36% of India’s GDP that year.

There is substantial variation across Indian states. In 2019, the less developed states in north and northeastern India had a higher burden from household air pollution than the more developed states in the west and south. And irrespective of level of development, states across northern India had a high burden of ambient particulate matter pollution.

Economic losses at the state level are associated with the number and the age distribution of deaths, and morbidity in each state and state GDP per worker. They also show the variation in economic loss due to premature deaths and morbidity attributable to air pollution as a percentage of the state GDP and find that poorer states lose a larger share of their GDP because of air pollution.

Delhi is one of the richer states and has lower levels of household or indoor pollution (mostly caused by cooking fuel). But, on the map, Delhi doesn’t look like other southern and western rich states. Delhi has relatively more severe ambient particulate matter pollution, especially PM2.5.

Delhi had the highest per-capita economic loss due to air pollution!

Air pollution leads to 10 times the deaths of malaria. Loss of productivity due to morbidity is at an even higher scale. And India is incredibly young, still growing in population and economic activity contributing to air pollution, and will have long-term consequences on human capital.

I feel a lot better about my focus on Delhi pollution. Though it affects me personally, and I have an emotional connection to Delhi; mitigating air pollution in India is one of the most urgent policy issues! But first, we need to understand why the air is so bad in Delhi.

3. Why Is Delhi’s Ambient Particulate Matter Pollution So Bad and Getting Worse Each Year?

The news about Delhi’s air pollution is dominated by stories of crop residue burning in the northern states of Punjab and Haryana, causing Delhi to turn into a gas chamber. But I grew up in Delhi, and the farmers in those states have been burning paddy crop residue for decades. The burning only takes place for two weeks each year. What about the other 50 weeks? Experts extrapolating from the Chinese experience usually blame industrialization, but Delhi’s industrial activity has shrunk as a proportion of all economic activity and has also been driven to the outskirts by regulation and court orders. Others blame economic growth and liberalization that led to an explosion of vehicles, an increase in industrial pollution, loss of tree cover and so on.

There isn’t a simple relationship between an increase in GDP per capita and pollution. As Indians get richer, indoor air pollution decreases, as the additional income increases access to cleaner domestic fuel. Delhi has one of the lowest levels of household air pollution. And southern states that benefitted the most from the liberalization-fueled economic growth have not experienced the same kind of increase in vehicular pollution.

Delhi’s transportation policy in the last two decades can be summed up as: construction of roads and metro to accommodate the dramatic increase in private vehicles because the Supreme Court of India killed Delhi’s functional bus system. And this increase in construction and vehicular pollution is the reason for such high, and increasing, levels of ambient pollution.

The main contributor to Delhi’s poor air quality is ambient particulate matter pollution, especially PM2.5 and to a lesser extent PM10. Road dust and vehicular population account for 58% of PM2.5 and 65% of PM10.

Sources of PM2.5 Emission Load in Delhi (2013-14)

Sources of PM10 Emission Load in Delhi (2013-14)

Less than 1.5% of India’s population lives in the NCR region, but it has over 4% of all registered vehicles. This increase is not just because Delhiites have gotten richer. Delhi and Mumbai have comparable populations, and Mumbai is richer. But Delhi has four times the number of private vehicles compared to Mumbai; and closer to six times if neighboring areas like Faridabad and Ghaziabad are included (Government of India Road Transport Yearbook 2019). Simultaneously, the absolute number of buses (and therefore buses per capita) have decreased in Delhi in the last two decades.

Ironically, the increase in pollution from the increase in the number of vehicles and road dust from construction are the unintended consequences of the activist Supreme Court of India trying to reduce pollution in Delhi.

Seeing Like a Supreme Court

It started in 1984-85 when a Delhi lawyer named M.C. Mehta filed a number of public interest litigation cases in the Supreme Court of India. In the 1980s, the Supreme Court had turned activist by diluting locus standi requirements (the ability/standing to bring an action before the court) and started pronouncing judgment in all manner of cases from air pollution to a self-appointing judiciary.

The court started by setting standards for gasoline, phasing out leaded petrol, eclipsing rules for phasing out decades-old vehicles, etc. In a drastic measure, on July 28, 1998, the Supreme Court ordered all commercial public transport in Delhi, which included about 100,000 buses, taxis and auto-rickshaws, to convert to run on a cleaner fuel, CNG (compressed natural gas), by April 1, 2001. It simultaneously ordered the Delhi government to create a bus fleet with 10,000 buses by 2001.

Delhi was historically a union territory, directly governed by the government of India. It got a new legislature in 1993 and didn’t have much state capacity, especially for large-scale municipal decision-making in the 1990s. The first term of the Delhi government saw three different chief ministers and a barely functioning executive. In 1998, when the Court ordered its new measures for commercial vehicles, first-time Chief Minister Sheila Dixit, leading an executive machinery that was barely five years old, couldn’t implement the orders in time. In April 2001, there wasn’t a big enough supply of CNG buses, CNG-enabled gas stations, CNG auto-rickshaws, etc. forthcoming. The result was Soviet-style shortages with long lines of drivers waiting for fuel.

The Economic Survey of Delhi 2002 reported that the Delhi Transport Corporation’s (DTC) on-road bus fleet reduced by 40% and average bus occupancy increased by 40% in 2001, compared to the preceding year. I started university shortly after the diesel bus ban and CNG conversion order came into play, and the lasting memory of my first year of university was figuring out how to get on and off overcrowded buses without getting groped. After 12-18 months, the general view in Delhi was to switch to private vehicles, either owned or for hire. After struggling for the first year in college, my solution was carpooling with five other friends. I wasn’t alone.

A second court order during that time froze the number of auto-rickshaw (three-wheeler scooter rickshaw) licenses that were issued in the city at 55,000. Delhi is a large and sprawling city, and while public and private buses covered the hubs, autorickshaws served as the last mile taxi for the poor and middle class. This freeze lasted until 2011 when an additional 45,000 licenses were issued though Delhi and its suburbs had grown many times over in size.

Another blow to the bus fleet came in 2011. A fatal accident involving a 14-year-old boy—the 61st victim in 2007 to be killed by the rash and negligent driving of one of these private Blue Line bus drivers—caused Judges Mukul Mudgal and P.K. Bhasin of the Delhi High Court to take suo moto cognizance of the matter after reading the news. The ordered over 2,000 private Blue Line buses off the Delhi roads because of rash driving. The Supreme Court upheld this madness.

The Blue Line operators brought the Court’s attention to the fact that the DTC bus service only had about 6,000 CNG buses, well short of the Supreme Court’s 1998 order of increasing the fleet to 10,000 CNG buses. Unmoved, the Delhi High Court ordered the Blue Line buses off the roads when the permits expired in 2012, and gave the Delhi government renewed orders and more time to increase the size of the bus fleet. Delhi is still short of that number. The Delhi government tried to salvage the situation by partnering with private buses to create a cluster bus service. Though these efforts were partially successful, Delhi residents are still facing a massive shortage of reliable public transport.

These actions by the Court decimated bus transport in Delhi, and the city never recovered. Delhi has fewer registered buses today than it did in 2001. This includes newer mini buses and private bus models. The government-owned and -run DTC has fewer buses today relative to 2001.

Unsurprisingly, given the shortage of buses and auto-rickshaws, Delhi residents started relying on private vehicles. The sharpest increase was in motorized two-wheelers (MTW). Between the 1997 freeze of auto-rickshaws at 55,000 and the increase in 2011 to 100,000, the population of Delhi increased by more than 45%, and the registered number of cars and MTWs rose by 250%.

During this same time period, the Delhi metro was constructed. Approved in 1998, the Delhi metro launched its first route in 2002. Since 1998, Delhi has seen the construction of 390 km of metro rail across all the routes serving 286 stations.

Though immensely successful, the Delhi metro isn’t a substitute for the bus fleet; it is a complement. This is due to the sprawling nature of Delhi unlike, say, Mumbai. The Delhi metro covers roughly 1,500 square km (approximately 580 square miles) in the greater Delhi area. It has helped Delhi residents cope with the urban sprawl and rising housing costs. But because there aren’t enough buses and auto-rickshaws to cover the last mile, residents who could afford them switched to private vehicles.

One second-order consequence of the increase in private vehicles was road congestion and long commutes. Consequently, the Delhi government and the government of India went on a road construction spree. Road construction is enormously profitable for politicians through kickbacks, and the builder-politician nexus is well established. Delhi residents were adding 1,000 private vehicles a day, and the consequent congestion was the perfect opportunity to increase road lengths.

In 2000, there were 2.5 million private motor vehicles in Delhi, which increased to just over 11 million in 2019. To accommodate this growth, Delhi’s road network also increased. Official reports suggest a decrease in road length in Delhi, often attributed to the success of the Delhi metro. But a more careful look at the road data in the latest Delhi Statistical Handbook shows that Municipal Corporation of Delhi (MCD) roads have not been reported since 2015. Using older MCD numbers and the latest numbers for other state/national highways etc. in Delhi, road length has increased by 57% since the 1997 Supreme Court order.

The increase in the construction of roads and metro is the reason for the increase in PM10 pollution, half of which is attributable to road dust.

Pandey et al. find that 59% of the 1.67 million premature deaths from air pollution in India in 2019 were from ambient particulate matter pollution, and another 37% from household air pollution. But, the death rate due to household air pollution decreased by 64.2% from 1990 to 2019, while that due to ambient particulate matter pollution increased by 115.3%.

As Indians get richer, household air pollution decreases, as higher incomes increase access to cleaner fuels. But in the absence of state capacity, good rules and standards and basics like a good public bus fleet running on clean energy, the burden attributable to ambient particulate matter pollution will likely increase. This is because as Indians get richer, in the absence of quick and reliable transportation, they will rely on personal vehicles, which means more road and metro construction and more vehicles to cover the last mile.

4. What Is the Best Way To Help Mitigate Air Pollution in Delhi?

There is a new class of environmentalism premised on demonizing economic growth as the reason for air pollution and the consequent evils. But the relationship between economic growth and air pollution is not so straight forward. One hundred years ago, London had worse air quality than Delhi today.

London solved this by getting richer, reducing its reliance on burning coal, building out a sewage system, transportation system, households switching to gas as cooking fuel, developing a waste disposal and management system, setting standard for vehicles and cleaner fuel, building an underground metro system and bus fleet, relying on innovation and entrepreneurship that developed devices to reduce household pollution and so on. But it took time and increases in both prosperity and state capacity made it possible.

I have tried to get a grip on the problem of air pollution in India, specifically Delhi, by quantifying it. I spent hours looking up the number for the increase in the number of private vehicles, the decrease in buses, increase in road construction and metro construction and so on. And yet, the point of narrowing down to the increase in cars in the last two decades is to understand the unwieldy and complex problem. It would be foolish to narrowly point to the increase in cars and then solve the problem by limiting the number of cars. Or to look at the increase in road construction and ban new roads. Or to blame economic growth that allowed a few million Delhi residents to afford cars. The increase in cars is the symptom or consequence of the larger problem—Delhi’s lack of cohesive public transportation for its residents. Delhi residents have a government that can build 10,000 km of roads over a two-decade period, but not procure 10,000 CNG buses or issue 10,000 licenses to private bus services.

To prevent further increases in pollution in Delhi requires developing a high-capacity government with the ability to introduce and manage a large bus fleet running on clean fuel, preventing the procurement rules and institutions that foster the corrupt builder-politician nexus, as well as a Supreme Court that doesn’t dictate policy orders without sufficient knowledge, a more functional municipal system, etc.

It takes decades, maybe centuries to develop high state capacity that can tackle commons problems, mitigate pollution and create a world-class clean public transportation system. And this requires increases in economic growth and government revenue as well as well aligned political incentives. The problem is there is no simple solution that can be easily implemented. Unlike malaria, the impact of air pollution cannot be avoided by handing out air purifiers. They they don’t even make a dent in lowering the hazardous AQI in Delhi. The problem can only be solved though better governance mechanisms and innovation. Innovation can take the form of better construction technology that doesn’t contribute as much to particulate matter pollution. Or by developing cleaner fuel for vehicles. Or through better carbon capture and particulate matter capture technology. But none of this is legible or predictable.

And it is not easy to know whether think tanks working on Delhi transportation policy, or think tanks working on judicial policy or for-profit companies working on clean fuel or clean construction technology will have the most impact. These solutions to air pollution don’t lend themselves to easy measurement and quantification. But just because the impact cannot be easily measured or compared does not mean these longer-term, less predictable and more complex institutional responses won’t have an impact. It simply means that demanding impact evaluation as the basis for philanthropic contribution is asking a question that cannot be answered.

Certain forms of knowledge and control require a narrowing of vision; this tunnel vision offers the advantage of bringing into sharp focus limited aspects of an otherwise very complex and unwieldy reality. This very simplification makes the phenomenon at the center of vision far more legible and hence far more susceptible to careful measurement and calculation on the one hand and to control and manipulation on the other.

- James C Scott

This is not to say that GiveWell is misleading us by listing the Malaria Consortium and the Against Malaria Foundation as its top choices. GiveWell’s calculation includes the impact per dollar and they find that it costs only $7 to save one child using antimalaria medicine and only $5 per malaria net. So even though malaria leads to one-tenth of the fatalities as air pollution globally, spending on malaria prevention may well be the highest impact per dollar for interventions we can calculate. The impact evaluation tells us that it saves most lives per dollar compared to other projects or interventions that can be easily calculated and compared, like giving vitamin A supplements to prevent blindness or training guide dogs. Air pollution, though a more pressing global policy problem, is not as simple.

6. Back to Malaria—Is It Really That Simple?

While writing this post, I also thought more about malaria and whether malaria prevention is more complex than impact evaluations lead us to believe. If legibility is the consequence of a narrowing of vision to make a complex problem tractable, then are these malaria mitigation interventions too simple?

95% of all malaria deaths are in Africa, and that malaria disproportionately kills children.

This is probably why the effective altruism community, which believes in helping those far removed from one’s situation, measures by lives saved per dollar when thinking about long-term and high-impact efforts, and rates malaria prevention charities so highly. In his latest column, Ezra Klein defends the basic principles of effective altruism and separates it from the SBF-FTX mess. He writes:

This is my annual giving column, so I won’t beat around the bush. I recommend donating to GiveWell’s four top-rated charities: the Malaria Consortium, the Against Malaria Foundation, Helen Keller International and New Incentives. These charities distribute medication and bed nets to prevent malaria, vitamin A supplements to prevent blindness and death in children and cash to get poor kids vaccinated against a host of diseases.

What sets these groups apart is the confidence we have in the good that they do. Plenty of charities sound great to donors, but their programs are never studied, and when they are, the benefits often disappoint. These organizations are different: Their work is backed by unusually high-quality studies showing that they save lives and prevent illness at lower cost than pretty much anything else we know of. (emphasis added)

It is impossible not to feel for the children in Africa dying from malaria. But suggesting that distributing nets and antimalarial medication is the best way to save lives and prevent illness compared to anything else we know is narrow. Regions outside Africa only account for 4% of malaria deaths. But I don’t see high use of mosquito nets and antimalarial medication in Europe and the U.S. Outside of camping equipment stores, I don’t think I have seen any mosquito nets bought or sold in the U.S. These countries don’t have malaria deaths because they have access to good public sanitation, clean water, electricity and healthcare. Malaria hits children in poor regions with low state capacity.

Common sense tells us that the best way to save lives and prevent illness is economic growth. But then how do we know for sure that economic growth in Africa will help reduce malaria incidence?

Look at the decline in malaria deaths in India since the big bang reforms in 1991, which placed India on a higher growth trajectory averaging about 6 percent annual growth for almost three decades. Malaria deaths declined because Indians could afford better sanitation preventing illness and greater access to healthcare in case they contracted malaria. India did not witness a sudden surge in producing, importing or distributing mosquito nets. I grew up in India, in an area that is even today hit by dengue during the monsoon, but I have never seen the shortage of mosquito nets driving the surge in dengue patients. On the contrary, a surge in cases is caused by the municipal government allowing water logging and not maintaining appropriate levels of public sanitation. Or because of overcrowded hospitals that cannot save the lives of dengue patients in time.

So, it seems bizarre to claim that these impact studies on distributing malaria nets prove “that they save lives and prevent illness at lower cost than pretty much anything else we know of.” Economic growth and high state capacity saves lives at a much higher scale, not just from malaria but from all infectious diseases. And malaria-affected individuals can be saved and illness can be prevented at very low marginal cost if we embrace the idea of economic growth and prosperity for all of humanity.

Economic growth helped save lives and prevent illness from ALL infectious diseases.

Sustained economic growth in India has saved an additional 405 lives per 100,000 in a country with 1.4 billion people. If India had the 1990 death rate from infectious diseases in 2019, an additional 5 million Indians would die each year. That’s the total estimated excess death toll from Covid in India. Economic growth in India has saved those lives every year. And as Indians become prosperous, the number of lives saved will increase without any additional spending on mosquito nets.

Perhaps I am focusing on the wrong part of GiveWell and Ezra Klein’s claim. I should focus on “at a lower cost than pretty much anything else we know.” Perhaps those recommending these charities as having the highest impact are doing so because they can be implemented and evaluated with confidence at a lower cost relative to efforts to improve state capacity and boost economic growth. Giving to charities that work on state capacity, institutions, public sanitation policy, economic growth, etc. is not a sure thing. Maybe they only increase the chances of economic growth by 5%. But with enough diligence and evaluation, we can be 90% sure that our dollars buy the additional mosquito net, and that mosquito net has a 70-80% chance of saving a life. So, this is less about the overall impact and more about “impact we know” or better phrased as “impact we can count and take credit for.” The Against Malaria Consortium’s website says they have raised $488,628,184, funded 223,421,135 nets and protected 402,158,043 people. Contributing to this institution a donor can calculate the number of lives they saved with their contribution. This is not just about legibility but also attribution. Each dollar donated will not just save lives but also assuage guilt, signal virtue and make one feel good during the holidays. Telling people about investments in clean construction technology hardly has the same effect at the holiday party.

It is not just philanthropy. In my conversations with Lant Pritchett (1 and 2) he argued that development policy and aid has been infected by attribution. We have long known that the first step to development in poor regions of the world is economic growth. But economic growth is neither easy to achieve, and when achieved not easily attributable to a single intervention.

India’s development trajectory changed when the reforms in 1991 ended the worst parts of socialist command and control, opened India to global trade and put in place several institutional changes for currency and macroeconomic stability, pushing India into higher growth for the next three decades. As a result, GDP per capita increased sevenfold, and about 250 million Indians—more than the total population of Brazil—were lifted out of poverty. All socioeconomic groups prospered because of sustained economic growth. India added approximately $3.6 trillion to its economy as a direct consequence of these reforms.

Lant Pritchett writes about the Ford Foundation investing in the Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations (ICRIER) in 1982. ICRIER is a nonprofit research center created “to foster improved understanding of policy choices for India in an era of growing international economic integration and interdependence.”

Suppose the Ford Foundation gave 36 million dollars (I have no idea what it really was but I strongly suspect this was the right order of magnitude and I just make it divisible) to support ICRIER.

Optimistically, suppose this gift increased by 50 percent the chance ICRIER was created and became an effective think tank (perhaps other funding could have come along, perhaps not) and suppose the existence and actions of this think tank increased by 10 percent the odds India adopted growth accelerating policies (my read of the situation is that it was higher). Then the expected value of Ford Foundation’s 36 million of support was 180 billion dollars (bracketing discounting), a 5000-fold return per dollar of investment.

Pessimistically, suppose the Ford Foundation funding only increased the likelihood of an effective think tank by 10 percent (someone else almost certainly would have funded it) and the impact of ICRIER on the likelihood of a growth accelerating policy outcome was only 1 percent, the investment still returns 100-fold—3.6 billion on 36 million.

Suppose instead the Ford Foundation had given 36 million in what many regard as the highest return individualized investment: girl’s education. There are hundreds of studies showing a positive return both to wages and to other outcomes—fertility, child survival, empowerment, etc. Let’s suppose, super optimistically, the return on this investment was 20 percent. This means an additional 7.2 million dollars.

But, Ford Foundation can take direct causal credit for the outcomes for these specific girls. They have the names of the girls supported. They can take their pictures and put them in their brochures. They could do an RCT and prove rigorously the increased benefits were the direct result of their grant.

The need for attribution in philanthropy has led to “rigorous impact evaluation,” and to conduct these impact evaluations necessarily requires narrowing and simplifying the problem into legible and calculable forms. The end result is claims that distributing malaria nets is the best way to save lives and prevent illness. Common sense tells us otherwise.

What About Charitable Giving?

This holiday season, you should send your charitable giving to save African children from malaria by distributing nets or medicines because it is a cause close to your heart or you have an emotional connection to the region or people. Only because you think it is important. Any other reason like impact and rigor is usually based on the most convenient calculation to make one feel better.

If you want the unemotional giving to have the highest impact on eradicating malaria, best to contribute to institutions working on kickstarting economic growth in Africa, or building municipal capacity to increase public sanitation, or developing vaccines and building state capacity to distribute malaria vaccines, or building hospitals and increasing the number of doctors and nurses in Africa. All these efforts help reduce the number of malaria deaths but also help improve the lives of Africans in many other ways.

If you want the highest impact intervention on lowering global mortality, reducing air pollution is a good cause. Once again, donating to institutions working on a range of solutions from transportation policy, urban policy, judicial reform to state capacity will have some impact. Investing in for-profit businesses and startups working on clean tech solutions is even better. London air got cleaner, not just from regulatory oversight, but from dramatic innovations towards cleaner fuel.

This view has affected how I support others working on complex problems to make the world better. I direct the India grants for Emergent Ventures - a fellowship and grant program supporting moonshot ideas and talent started by Tyler Cowen at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University. There is also an Emergent Ventures Africa program, let by the excellent Rasheed Griffith. You can read about the kind of moonshot ideas supported by the program at Marginal Revolution.

If you want to make the greatest impact in the long term, nothing can beat contributing to institutions working toward increasing economic growth and prosperity in poor regions like Africa and India. Increasing economic growth will help solve both malaria and air pollution. It will be your least attributable contribution, but the one with the highest impact. Economic growth in India is my personal moonshot project. I haven’t just bet my charitable giving, but my career on it. I lead the Indian political economy program at the Mercatus Center.

Really fantastic post Shruti. As someone working on helping India develop economically, I can really attest to the transformation that has happened even in the 6 years I have been here. You can see a tangible difference in the average person's lives.

That said, the lack of state capacity on things like metros, buses, buildings, educaiton, healthcare, piped water, etc. is absolutely holding millions of people

And as someone who tries to take the metro in Delhi, it drives me nuts how hard it is to do the last mile! Most people I know don't have my level of patience and just give up and drive. Simiilarly, I often think about how much each individual home in Delhi spends on water purifiers vs. what the cost would be for the government to just tax those same homes and build water treatment to each . I suspect it would save several orders of magnitude, but have not seen anyone do this calculations-maybe something you can suggest to one of your students!

This is very interesting reading about Delhi! I will make an argument for part of GiveWell's case that I think isn't covered here.

Part of GiveWell's argument for the causes it endorses is that they are things that private charity can do relatively better. To take a simpler problem, consider choosing between vaccinations and bednets. Vaccinations are very effective and nobody would argue that bednets are better. However, because it's so well-known, vaccinations are well-funded by governments, foreign aid, the UN, and large private charities like the Gates Foundation. (Also, there are trials for promising new malaria vaccines, but they aren't asking for private donations.)

GiveWell judged bednets to be relatively neglected and to have "room for more funding" because it's something private donors can do to make things happen without being overshadowed by bigger funders.

I would like to see more arguments in favor of alternatives to GiveWell's recommendations. But to be convincing, I think they need to be pretty specific: how can this private charity help? What does it do? Why is it a good cause? Charities devoted to legible causes will have the advantage in making persuasive arguments (at least to those of us impressed by math-based arguments), but there is certainly room for other arguments.

Perhaps we need more charity evaluators that take different approaches? Trust is a key issue here (another kind of legibility). I have seen alternative charities that seem pretty good, but they often don't publish enough information to understand what they do very well. As a stranger from another part of the world, I don't have the same confidence in them.

By contrast, "economic growth" is a broad abstraction. Investors don't invest in "economic growth"; they invest in specific companies that sell specific products and services that contribute to economic growth. As an abstraction, it seems too vague to fund - it's not really in the same category as a specific charity recommendation.

Something like "building hospitals and increasing the number of doctors and nurses in Africa" is a bit more specific, but Africa is very large and there are many charities. Some are surely better than others? One would want more specifics.

Few people are in a position to devote much time to charity evaluation - another way that there are likely many good charitable causes that aren't legible to us. Part of GiveWell's competitive advantage, whether you believe in their particular approach to evaluation or not, is simply that they are a knowledgable, trusted charity evaluator and there are few of them.