An economic puzzle of the Modi years : the hype is not followed by investment

The answer lies in the many kinds of political uncertainty, low and declining Gross Fixed Capital Formation, and the many quirks of Indian policymaking.

Prime Minister Modi declared a successful economic recovery post-Covid. A number of international agencies have dubbed India the fastest-growing economy. India has eliminated extreme poverty (below a dollar a day), a cause for celebration (while noting that defining “extreme poverty” as living on less than a dollar a day is what Lant Pritchett would call setting the bar so low it’s practically a trip hazard). PM Modi seems to be the most popular national leader in the world and is expected to sweep the polls this year. Everyone seems to be bullish on India. Except…well, Indians.

While there is no shortage of industrialists praising the Modi government and its economic policies, as a community, they don’t seem to be putting their money where their mouth is. Their reluctance to invest in longer-term plans paints a different picture, one of caution rather than celebration. How can I generalize across all businesses and sectors, you may ask. Have I engaged deeply with businessmen in India? Am I just another foreign-trained economist, criticizing Modi, being true to my tribe? Haven’t I heard the businessmen, in India and the world over, praising Modi? I have also seen the numbers for Gross Fixed Capital Formation.

Low Gross Fixed Capital Formation

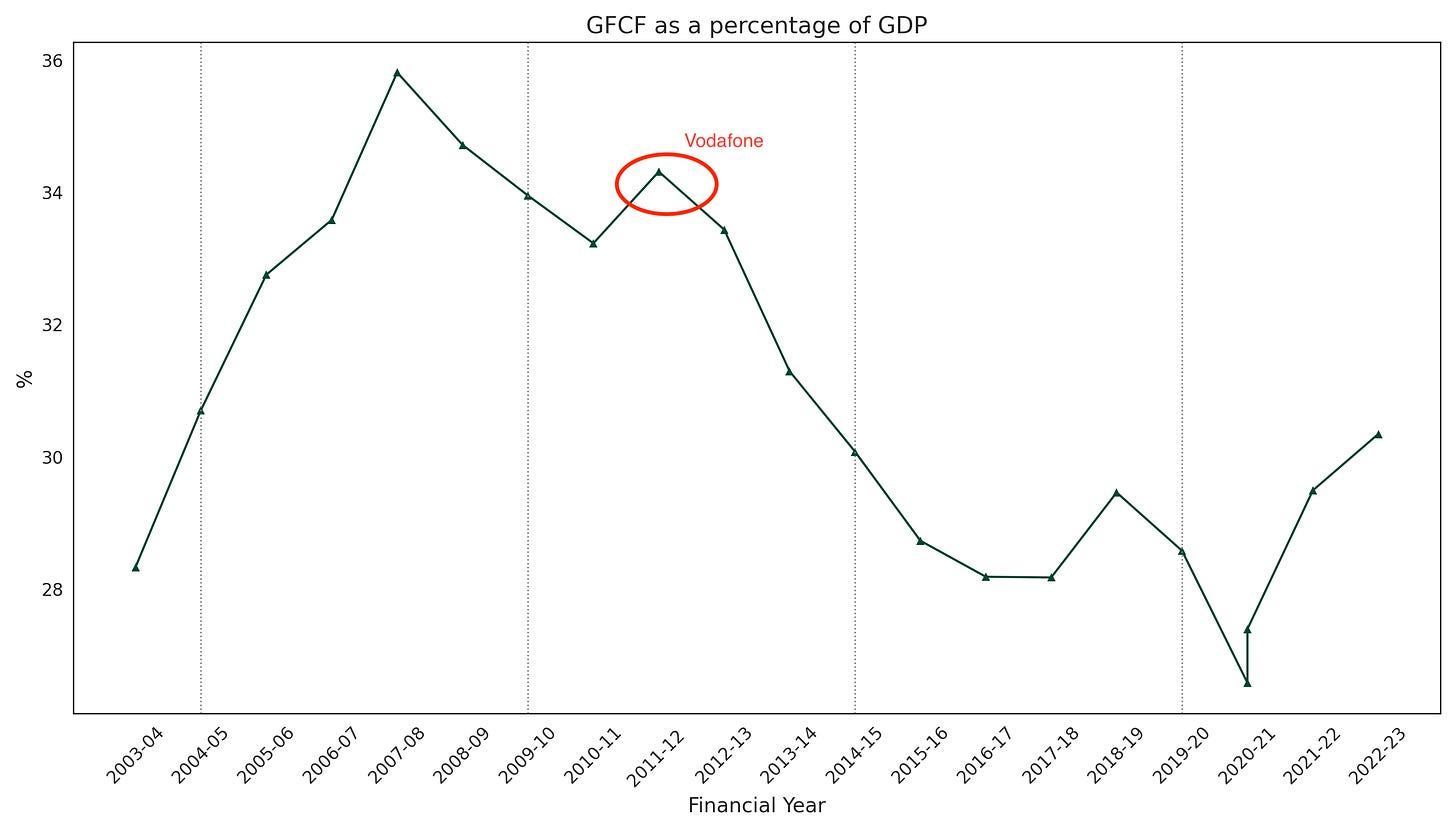

Economists care about what people do more than what people say. One way to compare how businesses and investors perceive the economic environment is by tracking Gross Fixed Capital Formation (GFCF), a fancy term for the total amount a country – individuals, firms, government – spends on long-lasting stuff. Think buildings, machines, and technology that businesses use to produce goods and services. Roads, airports, and train tracks the government lays. This also covers intangible assets like software and patents, and even the cost of sprucing up existing assets to boost their performance. But it’s not all just durable goods; sorry, some of your household’s prized new purchases won’t count. Most aspects adding to GFCF contribute to overall capacity maintenance, capacity building and expansion in the economy. During Modi’s tenure, GFCF as a percentage of GDP declined and has remained low until the post-pandemic recovery. In fact the highest level of GFCF as a percentage of GDP during the first nine years of Modi’s leadership is lower than the lowest level in PM Singh’s tenure.

GFCF is a big deal because it’s essentially the economy’s growth engine. Investing in new or better assets pumps up production capacity, potentially leading to more jobs, higher incomes, and economic expansion. Government spending on infrastructure also gets lumped into GFCF, improving efficiency and productivity across the board. But GFCF isn’t just a growth lever; it’s also a peek into the collective mindset about the future. Think of tracking GFCF akin to placing a stethoscope and listening to – their dil ki awaaz – or what investors’ heart or gut feels about the future.

When people believe the economy is on an upswing, they plan for that rosy future. For example, if economic growth hints at longer lives, hospitals might gear up to treat more seniors by adding more wards. Likewise, if companies anticipate a bustling economy full of exuberant consumers, they’ll ramp up production to meet expected demand. We typically look at GFCF as a percentage of GDP because, as an economy grows, the requirements and expectations for fixed investment also change.

This is the trend of GFCF as a percentage of GDP for the last four union governments – with PM Manmohan Singh from 2004-05 to 2013-14 and PM Modi from 2014-15 to 2022-23. The beginning of this decline in GFCF as a percentage of GDP predates Modi, but it has never recovered.

WTH happened in 2011-12?

Because of a series of unfortunate events, Pranab Mukherjee ended up as finance minister and managed to give one last parting gift straight out of Indira Gandhi’s economic legacy.

In 2007, Vodafone acquired a stake in Hutchison Essar via an offshore deal. The Indian tax authorities, never ones to miss a party, slapped a hefty tax bill on Vodafone. After zigzagging through courts and appeals, in 2012, the Supreme Court of India held in favor of Vodafone that no taxes were owed in this offshore deal between foreign entities.

Enter Pranab Mukherjee, stage left. In a move that would make his fellow Comrades proud, he amended the Income Tax Act to ensure these transactions were taxable, not just in the future, but with retroactive effect all the way back to 1962, sidestepping the Supreme Court’s verdict. This wasn’t just moving the goalposts; it was declaring a new game had started decades ago, where only the red team won.

And Vodafone was not the only victim, there were others, like UK’s Cairn Energy. Suddenly, investors found themselves navigating a landscape where today’s rules might not apply tomorrow, and deals completed under a past set of rules were fair game for taxation, a scenario no one could have, or indeed did, foresee. The result? Investors, whether parked domestically or eyeing India from abroad, dropped India like a hot potato when it came to big, difficult to undo, long-term bets.

The Vodafone case was followed by more drama for big businesses, as the Supreme Court canceled licenses granted for telecom spectrum and mining etc., acquired through bribes. When the second UPA term ended in 2014, it was clear that businesses were not in a mood to bet big on India. Though the blame is correctly placed on Pranab Mukherjee, leftist coalition partners, a polyvocal cabinet, and therefore PM Manmohan Singh, all this happened during 2011-14.

Since then, a decade has passed; however, the Modi government never managed to revive GFCF as a percentage of GDP. Enormous expectations were placed on the Modi government in 2014: (1) Modi campaigned on an economic development and progress agenda; (2) his party won a clear mandate to form the government without relying on pesky coalition partners; and (3) he was the clear leader within his party, with a singular voice, without any party politics within to undermine his economic agenda. The expectation was that all the uncertainty that came with the coalition politics that Singh couldn’t manage would be a thing of the past.

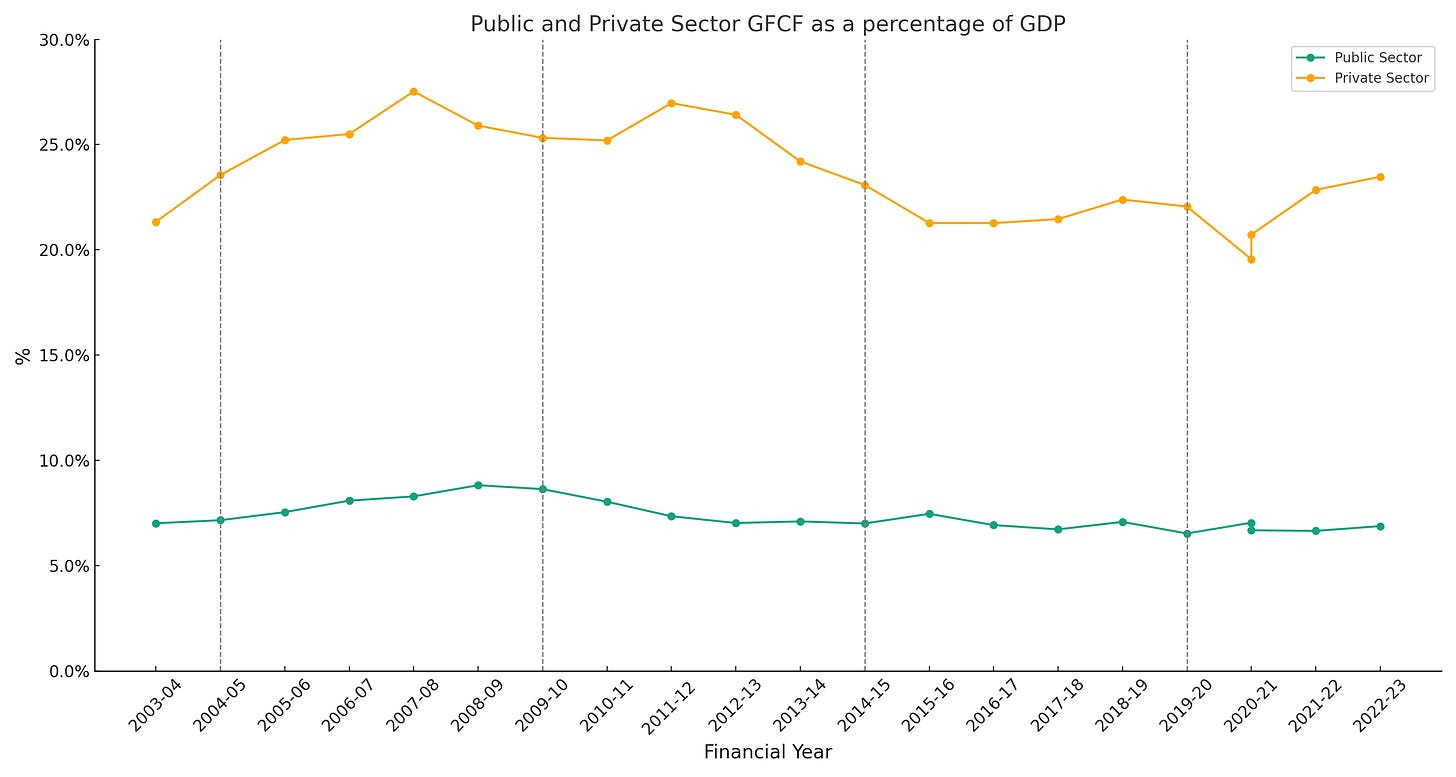

But what is puzzling is that GFCF as a percentage of GDP never recovered from what happened towards the end of Singh’s tenure, even at its highest levels during PM Modi’s tenure. And the public sector part of GFCF has been pretty stable, and the decline really came from the private sector not going back to the old levels.

One reason to compare the GFCF under Modi to the Singh years is the recent white paper released by the Modi government, which argued that when Modi took office the economy was “in a fragile state; public finances were in bad shape; there was economic mismanagement and financial indiscipline; and there was widespread corruption.” And over the last decade the Modi government has managed to, “restore the health of the economy and make it vigorous and capable of fulfilling the growth aspirations of the people”. If the basic argument of this white paper is correct, and the Modi government has indeed cleaned up the mess of its predecessor, why hasn’t GFCF as a percentage of GDP caught up and even surpassed the 2011 level?

Now there are a few possibilities put forth by the press, government officials, etc. First, that the GFCF at 30-35% of the GDP during the Singh years was just a blip, and largely unrealistic, and perhaps even driven by the low-interest rates leading up to the financial crisis. And the current trend is the correction. This doesn’t quite hold up well because the dip in 2011-12 is much sharper than what happened during the 2008 crash. And the banking sector seems to have recovered from the worst problems of the 2008 global financial crisis. In fact, the recent white paper makes a point of discussing the big cleanup that was required, and according to the government successfully completed.

A second explanation is that this has little to do with domestic policy and is driven by the global slowdown, which only recently picked up after the pandemic. This explanation also does not add up. Take, for instance, Bangladesh, which is also a fast-growing economy, with GDP per capita at Indian levels. Despite being a smaller economy and even more vulnerable to global trends, it seems to have increased its share of GFCF as a percentage of its GDP. (Note this graph has slightly different numbers because I am using World Bank data, calculated for the calendar years which are different from India’s financial year used in the first two figures).

Is India growing?

YES! And depending on who you ask, somewhere between 4-7 percent in the last few years. (The drama and contention around the GDP numbers is a long story, and I don’t want to get into that mess right now. Perhaps in a future post).

Then why aren’t people investing?

If we look at what happened since 2014 until the pandemic as a continuation of the trend started by the Vodafone debacle, then the answer is that they are facing too much regime uncertainty even though Pranab Mukherjee has left the stage. This seems odd given that India has had a single-party government since 2014, with an extremely popular prime minister at the helm. And in the last ten years, Modi governments have not been polyvocal; they speak in one voice, and that voice is Narendra Modi’s. So, what kind of uncertainty are we talking about?

Let’s think about regime uncertainty that presents itself in a few different ways - political/electoral uncertainty, policy uncertainty, and in some cases foundational uncertainty. Though Modi managed to remove the electoral uncertainty from the table, the last ten years have been mired in a lot of policy uncertainty, usually by the Modi government’s own doing.

Electoral versus Policy Uncertainty

Think of some of the fastest-growing places in the world, Shanghai, Hong Kong, Seoul, etc. Skyscrapers seem to be a mainstay. What will it take for Mumbai or Bengaluru to build more skyscrapers? A certain amount of demand for office space, which given the real estate prices seems to exist. And access to the financial, physical, and human capital it takes to build a skyscraper, which also seems to exist in these big Indian cities. Why aren’t India’s builders building more skyscrapers, even in places where the local laws will allow it?

It seems reasonable to assume that a 100-storey skyscraper will take longer and cost more than building a 10-storey office building.

One reason builders might pause, even those who are bullish about a metropolitan area and demand for skyscrapers, is policy uncertainty. Now we’re talking about regulations that dictate how tall your building can be, what materials you’re allowed to use, what kind of safety codes, fire codes, and environmental codes are in play, how many inspections will be required, and so on. Policy uncertainty is planning your skyscraper based on a certain set of building codes, only to find those codes are as stable as a house of cards on a windy day. A surprise regulation here, a new kind of inspection system there, a new kind of tax, or a change in tax classification applied to skyscrapers, and suddenly, your well-calculated budget and timeline read like fiction. If these are evolving, or can be changed arbitrarily, and without the input of builders, then builders will be cautious before planning a skyscraper. Maybe they settle for building the ten-storey office building instead.

A way that builders, especially in India, solve this problem of uncertainty is through political connections. If you are assuming honest businessmen at work, think lobbying, campaign finance, etc., and if they are closer to real-world builders in India, then explicit corruption, bribes, kickbacks, Swiss bank accounts etc., to make sure that the codes on which the blueprint was made won’t change, no new regulations or inspections will be introduced, that the police will get rid of any environmental groups protesting, and so on.

But India is an electoral democracy. What happens if the politician you bribed is no longer in office? This brings us to political uncertainty. Often, even if the politician changes, the party platforms are like firms, which have a longer life and can commit to more durable promises. So, builders don’t just have connections with individual politicians but with political parties. But if there is a lot of uncertainty over which party will win, if a single party will form the local or state government and so on, then the builder will either wait until there is more certainty or build something that can be completed quickly, ideally within the current electoral cycle. It’s the unpredictable nature of who’s in charge and what they’ll do next that can make or break the timeline and cost of your skyscraper.

While corruption and kickbacks are the way business is done in many places, including India, they bring their own kind of uncertainty. First is from whistleblowers, nonpartisan bureaucrats, opposition politicians, etc., waiting to unravel a “deal.” Another possibility, connected to policy and political uncertainty but still following a slightly different cycle, is judicial uncertainty. In sensible countries and systems, the judiciary enforces contracts, provides stability, maintains the rule of law, and prevents the government from enforcing arbitrary rules. In this sense, the judiciary enforcing contracts and conducting a review of pernicious and capricious regulation is the protection for builders. However, what happens if the judiciary is also changing and venturing into new areas? A “populist” court decides that the environment is very important and allows environmental protestors to get an injunction against the skyscraper even if the builder followed the existing codes. Or a major deviation from precedent, a new interpretation of the existing building codes to further the courts’ populist environmentalism. Or if the court decides to not only investigate the corruption charges but also demolish the buildings if the inspections and permissions were “bought” from those in power.

There is yet another possibility. Think of it as the ground beneath your skyscraper. It should be solid, right? But what if, suddenly, this ground could shift, not because of an earthquake, but because the soil and rock formation itself might change? This isn’t just about a surprise inspection; it’s about waking up to find that the very essence of property rights, the way you conduct transactions in your business, and your business model might be up for debate. It’s a bit like playing a game where the rules aren’t just changing; they might be rewritten entirely, leaving you wondering if your skyscraper will still be standing tomorrow. If parliament decides that the city where you are building the skyscraper is no longer part of a state but is a separate union territory directly under the federal bureaucracy. Or a global pandemic that stalls all business. Or if during such a pandemic, Indian regulators impose a lockdown that is so long and stringent, that businesses have to completely change to work-from-home policies. The model of business changes so drastically that there is no longer a demand for a skyscraper in the business district. Now we’ve got some foundational uncertainty, no pun intended.

Now imagine not just building physical skyscrapers but metaphorical ones in the world of investment and economic growth. Imagine, if you will, you’re about to embark on this grand project, but there’s a twist—not everything is as stable as it appears.

Though I have tried to separate the kinds of uncertainty faced by businessmen in an economy, these things are interrelated. Take, for instance, a policy like demonetization. Though it is a policy, issued by executive notification, eventually passed by an ordinance, with a statute enacted months after the announcement was made. If 86% of the cash notes, which is the blood in the veins of the construction business, is suddenly demonetized, builders cannot pay any of the vendors and get inputs. The fact that building is a cash business automatically makes them suspect, at the very least until they can prove that the cash dealings were completely legitimate. And none of the vendors can keep their promises in the short run, and in the long run, many may not survive because they don’t have access to similar amounts of bank credit and lost their cash options during demonetization.

The problem is not just demonetization, which is almost universally acknowledged as a disastrous policy, but that even the policy reforms the Modi government has considered a big success are served with a side of policy uncertainty. Exhibit A: the Goods and Services Tax (GST). Billed as a transformative leap toward a “Good and Simple Tax,” the GST aimed to knit India into a single, seamless market, free from the labyrinth of state taxes and cesses that had traders pulling out their hair and wallet at every checkpoint. Yet, in a turn that would perplex even the most ardent optimist, India rolled out with not one, but seven distinct non-zero GST rates, 0.25 percent, 1.5 percent, 3 percent, 5 percent, 12 percent, 18 percent, and 28 percent. Plus a bonus round of cesses – I stopped counting after 21 different cess categories and rates.

And then comes the existential dread, not over the meaning of life, but over whether a KitKat is a biscuit or a chocolate because, of course, biscuits are taxed lower than chocolates. Pepsi’s Nimbooz stirs up another conundrum: is it lemonade or pulp juice, each quenching thirst under a different tax bracket? And let’s not start on the barfi debate—how plain is plain enough for the 5% tax rate before dry fruits drag it to the 12% rate or chocolate shoves it into the 28% category? The GST Council donned its halwai hat to decree that chocolate barfis are, in fact, barfis, thus sparing them the excesses of chocolate tax. Since its inception, the GST council has changed the rates of over 500 goods and services through the 51 council meetings, each tinkering with the rates in a quest for everything but simplicity and certainty. This isn’t just tax policy; it’s a full-blown classification and identity crisis that can leave businesses in a state of bewilderment over the true tax bill. On the face of it, it looks like one area of policy reform and is an improvement over past tax systems, but the uncertainty of the new form impacts virtually all the goods and services in the economy.

But isn’t Indian infrastructure much much better?

Indian airports, train stations, roads, etc. are much better than before. Anyone who travels to India 3-4 years apart can immediately feel the change. But the reason is related to the above point of policy versus electoral uncertainty.

When the government contracts with a large infrastructure firm like Adani or GMR etc., one of the big questions between winning the project and completing it is political uncertainty, because these are government contracts for large public projects that are undertaken by private sector infrastructure companies. Modi’s ten years in office, especially as a strong voice with a clear mandate, made it possible to keep these promises.

All the permissions, environment clearances, etc. come from the same place, and the locus of control is the prime minister’s office. In the previous Singh government, for instance, the lack of coordination between different ministries was a real problem. The cabinet was a reflection of the coalition government, and large projects were endlessly stuck waiting for environmental clearance.

So, the argument is not that India is not building these capital assets, or that they are not improving. It is that the private sector is not making investments and building for the future with the same fervor as it did in the past. And this is despite the relatively high political or electoral certainty offered by the Modi government.

While large firms like Adani and L&T have the certainty required for large government-funded infrastructure projects, it is the smaller players who seem cautious. Households that need to build another room or floor are waiting instead of building. Businesses that need to expand capacity are not building the assets required for that expansion and so on.

Why is GFCF improving since 2021? What changed?

During Modi’s tenure, GFCF as a percentage of GDP has been low, even declining, there is an uptick since 2021-22. First, let’s go back to Vodafone because that story didn’t end with Pranab Mukherjee’s amendment in 2012. Vodafone didn’t appreciate India’s retroactive tax grab, so it invoked an India-Netherlands investment treaty to drag the dispute into international arbitration. In 2020, the Permanent Court of Arbitration sided with Vodafone, deciding India’s retroactive application of tax rules didn’t play fair with promises of equitable treatment. The court ordered that India should back off the tax penalty and cover Vodafone’s legal tab.

By August 2021, good sense prevailed, and India signaled a change of heart, scraping the retroactive tax bill, Vodafone’s included, and return any tax and penalty it had already collected. This pivot became official with the passing of the Taxation Laws (Amendment) Act 2021, also benefiting other firms like Cairn Energy after years of litigation.

Could it be intangible assets?

But turning the clock back on the wreckage caused by retroactive taxation in 2012 is not the only thing that changed in 2021. An important part is clearly the share of intangible assets in the economy that are now growing faster than ever. Intangibles included in GFCF are assets like software, patents, branding, etc.

If we go back to the example of the skyscraper, then think of the design and the blueprints created by architects for these skyscrapers, or the new software written to run the elevators at high speeds, and the brand value that attracts tenants and investors.

Intangible assets, such as software, intellectual property, and brand value, are not bound by the same physical constraints as skyscrapers. But the other aspect is that these assets are more easily scalable. The software written for running the elevators in one skyscraper can be used across different buildings. And a lot of the growth in India has been in developing software. SaaS startups in India, driven by venture capital coming in from abroad, have been part of this growth of intangibles.

Moreover, the characteristics of intangible assets that make them valuable - scalability, sunk costs, spillovers, and synergies - are also what set them apart from physical assets. The ability to use intangible assets repeatedly across different contexts without significant reinvestment is a unique advantage that physical assets don’t always have. While sunk costs can be a challenge for both types of assets, the nature of these costs is different. For intangibles, sunk costs are more about the time and effort invested in research and development of the asset. Compare this to the sunk cost of physical materials and labor used in construction. And the intellectual property, even when a project fails, can be more easily adapted to other uses, whereas the physical materials used for the foundation of a building that never got completed cannot be as easily repurposed. Jonathan Haskel and Stian Westlake detail these aspects of scalability and sunk costs of intangibles. But there are additional elements, like spillovers and synergies of intangible investments that extend beyond the investing firm. While a physical structure might increase the value of surrounding properties, it’s not the same effect as an innovative software or platform that can be utilized by others in the industry.

However, this doesn’t mean that investing in intangibles is free from uncertainties. The rapid pace of technological change, for example, can quickly render some intangible assets obsolete. Regulatory changes around data privacy, intellectual property rights, or digital marketplaces can also have significant impacts on the value of intangible assets.

Coming back to India, there were some major changes in the last few years that built India’s digital public infrastructure. Though it started in 2009, by 2016 it was clear that the biometric identity offered by Aadhaar would eventually cover all Indians. However, two other things happened in 2016. Jio Reliance offered 4G internet and data plans at extremely affordable prices to Indians, with the promise of covering all of India. And second, the Unified Payments Interface, a real-time payment system that allowed users to transfer money across multiple bank accounts. The combination of these three platforms led to the creation and expansion of what is now known as the India Stack. By 2018, cheap data provided at scale was clearly here to stay. UPI had launched its updated version that included the now ubiquitous QR codes. Updates and upgrades to the India stack started to include Digital Locker, electronic KYC (eKYC), digital signature on demand (e-Sign), and Direct Benefit Transfers (DBT), etc. And by 2022, the UPI was combined with the Open Network for Digital Commerce, ONDC, making it one of the most interoperable systems in the world. With this digital public infrastructure and a pandemic lockdown making coordination costs even higher, India’s SaaS and app-based sector has taken off.

The venture capital fueling this is driven by the internally based funds, and a lot of investors ask start-ups to form a Delaware or Singapore holding company before they are willing to invest. And SaaS-based startups require very little brick-and-mortar investments, unlike a manufacturing firm like Foxconn, making investors more likely to invest in these ventures even in a climate of policy uncertainty.

How does this impact India’s future?

Going back to the skyscraper metaphor, if there is too much policy uncertainty, then either the businessman won’t build anything, or if in dire need of expanding capacity, then build a ten-storey office building. The builder, in turn, won’t hire engineers, workers, and architects at scale and instead do it piecemeal. And the consequence of that is that these businesses cannot get the big benefit of economies of scale. A large part of the fixed cost investments that businessmen bear in the future, is to find the right scale at which their marginal cost will reduce. But if there is too much uncertainty that prevents businesses from taking on large fixed costs, and this is done piecemeal, then 10 small factories will never have the economies of scale of one big factory.

For India, this is a far worse outcome than anywhere else. India naturally offers economies of scale in virtually every sector because of sheer numbers. Even the most niche products and services can find enough patrons to make the project viable. And not being able to capitalize on that natural advantage is a shame. And second, India is in desperate need of better infrastructure and capacity building at every level, given its growth rate and ongoing structural transformation, and urban-rural migration. Without the private sector willing to engage in long-term plans, at scale, this kind of growth and transformation will be difficult to sustain.

The only way to avoid this kind of policy and political uncertainty is through a strong adherence to principles of the rule of law. To reform regulation such that the identity of the individual businessmen/bureaucrat/politician no longer matters. These days rule of law has come to be associated with “foreign” and “liberal” values and are seen as an attack on the government and political integrity of India. That such talk of liberalism only serves elite think tank interests or opposition politicians but gets in the way of everyone’s business. But no matter what Indians say they believe, they aren’t making long-term investments with these homegrown exception-based rules. To invest, they want certainty, like any other individual and businessman across the world. And the micro-level policy certainty they are looking for can only be possible with a stubborn attachment to meta-level rule of law.

Rule of law and Certainty

To be clear, there can be a divergence in the short term between certainty and rule of law. Take for instance the case of the Electoral Bonds Scheme rolled out in 2017 by the Modi government.

Think of these bonds as a kind of promissory note, for funding political parties anonymously and without using cash transactions. You could pick these up from certain State Bank of India branches (owned and controlled by the Government of India), and drop them into a political party’s hat, and no one (well…) would be the wiser about where the money came from or who it went to. The bonds came in sizes ranging from Rs 1,000 to Rs 1 crore, and parties had to cash them in swiftly, within 15 days. The idea was simple: this would clean up political donations by funneling them through banks instead of under tables.

The government lauded the anonymity feature as the best method of cleaning up campaign financing without bringing in scrutiny and political retribution. Critics felt the anonymity actually muddied the waters, letting donors, with their identities hidden, potentially sway politics without oversight. Even the big guns, the Reserve Bank of India and the Election Commission, waved red flags, hinting at risks like money laundering and foreign interference.

The bigger problem, however, was not transparency, but asymmetry. The transactions were anonymous to the general public, and opposition parties, but not anonymous to the Modi government and therefore to the dominant political party, BJP. The government not only knew who made and received the payments, its biggest bank was charged with keeping track of every single transaction.

Naturally, the scheme was challenged in court, and India’s Schrödinger Supreme Court, wanting to be both independent and pliant to the government at the same time, chose to postpone hearing the matter. Fast forward to February 15, 2024, and the Supreme Court calls game over, ruling Electoral Bonds unconstitutional. Their reasoning? Voters have a right to know who’s funding their politicians. This verdict wasn’t just a slap on the wrist; it was a directive to pull back the curtain. The State Bank of India was told to hand over the records of these bonds to the Election Commission, which in turn, had to make them public.

This moment was hailed as a win for transparency in political funding, a reminder that in a democracy, knowing who’s behind the curtain is non-negotiable. Rule of law prevailed in India.

If the decision had come in 2017 or even 2018, then both rule of law and certainty would have prevailed in India. But waiting almost seven years to pronounce judgment, and looking the other way when billions of rupees had exchanged hands, gave a sense of legitimacy to the scheme. And now all the political deals made in the last seven years using electoral bonds have suddenly become uncertainty.

When rule of law and certainty align…. Inflation Targeting

The odd thing is that the Modi government did manage to control certain types of uncertainty that have plagued India for a long time - inflation uncertainty - and also managed to comply with rule of law and create good institutional design. This was done while reforming monetary policy, no less, moving India to an inflation targeting regime.

The primary objective is to keep the inflation rate within a target range, which is currently set at 4% with a tolerance band of +/- 2%. For this a Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) was created in 2016, and its job is to maintain inflation between 2% and 6%. The MPC does this by setting the repo rate - the rate at which banks borrow money from the RBI - to target the inflation rate. Changing this rate is how the MPC hopes to influence what banks do next, which in turn, affects how much everything costs, how easy it is to get a loan, and ultimately, how fast prices rise or fall.

A mix of RBI insiders and government appointees, six in total, gets together at least four times a year and every member of the MPC gets a vote on where to set the repo rate, and if they ever tie, the RBI Governor breaks it. They keep everyone in the loop by publishing minutes of their meeting after a two-week cool-off period.

The design of the MPC and the transparency associated with the committee votes has brought much needed certainty and stability to Indian investors and consumers and helped form inflation expectations.

India needs this kind of reform, that brings institutional stability and policy certainty in virtually all areas, not just monetary policy. Double-digit inflation is very much a thing of the past in India, and the real game changing reform was brought in by the Modi government. Incidentally, keeping inflation low and predictable is great for investors, and also an electoral win. Advisors of Modi would do well to remember the success of MPC and replicate the stability, certainty, and transparency it fostered across other areas of the economy.

A few points.

(1) Glass half full or empty? You call the recent rise 5% point rise in the investment ratio "an uptick." One might just as well have called it "a promising rebound," depending on mood and ideological inclination.

(2) You emphasize factors like regulation and policy uncertainty that (while important over the long haul) may not have changed much between the last government and this one, and which therefore cannot explain the fluctuation in investment. Attributing macro-cyclical fluctuations to slow-moving structural factors seems to be a typical category error in "Washington Consensus" type thinking. To the extent the Vodaphone incident caused an exceptional spike in uncertainty, that was, as you say, the work of the previous government.

(3) You mention but do not make enough of the horrible state of the financial sector at the end of the last government. Cleaning up the mass of bad debts took time and seems to have set off a severe credit squeeze. That is the sort of macro-cyclical shock that would provide a plausible explanation for the cycle in investment.

If rule of law is the big problem in India, why is the gross capital formation higher in bangladesh? We have worse rule of law on all possible metrics. Due to the energy crisis of 2021 the central bank banned PRIVATE banks from buying new cars. You Indians can't us when it comes to madness.

I think it's unrealistic for India to achieve rules based capitalism. It's better to go down the deals based capitalism route which was how the rest of Asia industrialised. Although I agree with you that you need radically decentralise power to introduce fiscal constraints and a more competitive deal making environment.