Demography, Delimitation, and Democracy

One person one vote, and other questions Indians must confront.

In August 2022, I gave a talk titled “Demography, Delimitation, and Democracy,” about the impact of freezing the electoral constituency sizes India based on population numbers from the 1971 census. The Indian population has grown, and its internal demographics have changed significantly in the last half-century, which has led to malapportionment, which is the asymmetry between the shares of electoral constituencies relative to the shares of the population for given geographical units (usually states).

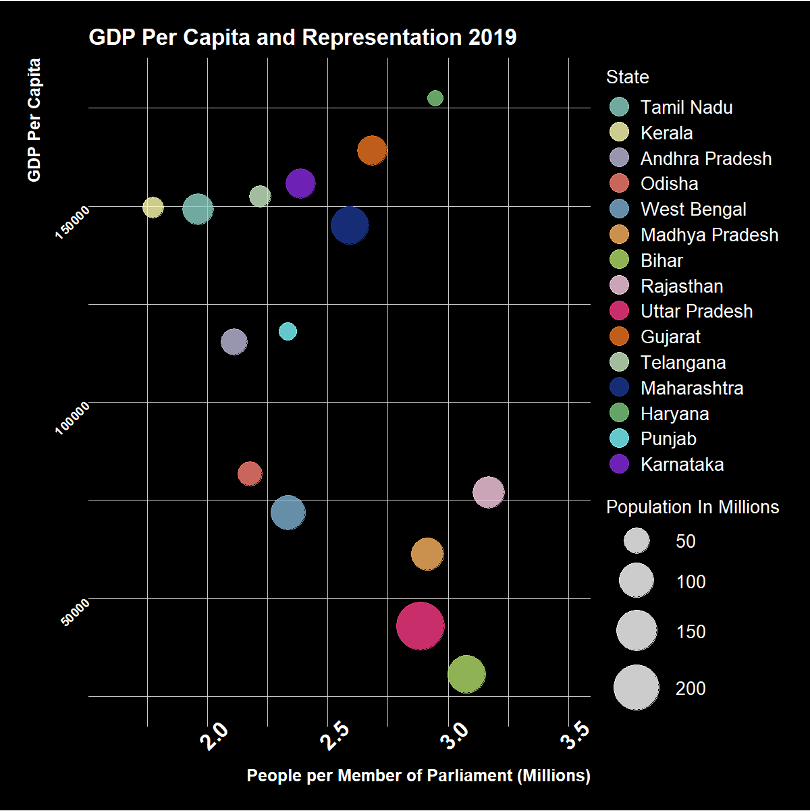

Malapportionment is quite severe in India. At the extremes: In Bihar, one Member of Parliament (MP) represents approximately 3.1 million citizens. An Uttar Pradesh MP represents approximately 2.96 million citizens. A Tamil Nadu MP represents approximately 1.97 million citizens. And a Kerala MP represents approximately 1.75 million citizens. Consequently, India is no longer living up to its fundamental constitutional principle of “one person, one vote.”

My friend Amit Varma asked me to discuss how India ended up at this point on his excellent The Seen and the Unseen podcast. On the episode (#336), we discussed the problem of delimitation frozen to 1971 census numbers, the design problem with Indian bicameralism and India’s fiscal centripetalism. Since I am currently working on two papers on the topic, I thought I would add some of the data visualizations from my talk last year in a Substack post to supplement Amit’s podcast show notes.

Constitutional Design

Delimitation refers to the action of fixing the boundary or limits of something. In Indian politics, it means determining the number of constituencies, their size in each state, and their boundaries. All three decisions carry significant political consequences. Delimitation Commissions, separate from an Election Commission that conducts elections, are established to understand, and capture, how the country’s demographics are changing, based on decennial census data. Delimitation Commissions provide the roadmap for how the country needs to change electorally — in other words, how many new constituencies need to be added/subtracted in a given state, and/or how their boundaries need to be redefined.

The constitutional provisions governing proportional representation in India are Articles 80-82 for Parliament, the main focus of this post and the podcast. You can assume a similar principle at work for state legislative assembly seats (Articles 170-171). One exception is Union Territories (UT), where proportional representation is not mandated. Parliament decides the number of seats for Union territories and small states with populations of less than 6 million.

Article 81 requires that for the Lok Sabha (lower house/house of the people) each state receives electoral seats in proportion to its population and allocates seats in a way “that the ratio between that number and the population of the state is, so far as practicable, the same for all states.” The 1950 constitution capped Lok Sabha seats at 500 and allowed a maximum of one Member of Parliament (MP) per 750,000 population.

Article 80 capped the maximum number of Rajya Sabha (upper house/council of states) members from states at 238, with an additional 12 members designated for functional representation or nomination. However, the most interesting aspect of Indian bicameralism is that the original constitution allowed for no malapportionment in either house of Parliament. It required that Rajya Sabha members from states also be chosen by the state legislature “in accordance with the system of proportional representation by means of the single transferable vote.” This differs from other systems, like the U.S., where each state, irrespective of population, gets the same number of electoral seats in the upper house, e.g. two Senate seats per U.S. state.

And since populations grow, and not evenly across all constituencies, Article 82 provided for redistricting based on the numbers from each decennial census.

The original constitutional scheme envisaged a perfectly apportioned Parliament, where both Lok Sabha and Rajya Sabha members for each state were in proportion to the population of the given state (though elected through different processes - direct versus indirect).

This system worked well, albeit with complexity, in the first two decades post-independence. Census data were used for redistricting and Delimitation Commissions were set up to allow seats to states as well as to draw boundaries. The main challenge in the initial years was threefold: (1) states joining the union and creation of new states, (2) reorganization of states, and (3) fast and uneven pace of population growth across states. To manage this, seats were added to Parliament and state legislatures. The Seventh Amendment (1956) increased the seats to 520, and the Thirty First Amendment (1973) brought it to a maximum of 545 seats. Currently, the Lok Sabha strength is capped at 552 seats.

How did India end up here?

Like many terrible changes in the Indian Republic, this one can also be traced back to the Forty-Second Amendment to the Indian Constitution, which in 1976, froze the number and boundary of constituencies in the Lok Sabha (Article 81) and state legislatures (Article 170) according to the population numbers from the 1971 census. The freeze was fixed for a period of 25 years, until the 2001 census.

The ostensible reason was uneven population growth. The politicians from southern states of India claimed that they more strictly and successfully followed the Union government’s population control mandate compared to the northern states. As a consequence, they alleged, that they were electorally and politically penalized for complying with the Union government mandate.

However, India’s original constitution was designed to address this problem. Both the Lok Sabha and Rajya Sabha were supposed to adjust seat share across states based on proportional representation, direct and indirect, respectively. So uneven population growth was not the real reason because the seat share in both Houses of Parliament would adjust based on population and any malapportionment would be eliminated after every census.

The actual reason was that India was a bicameral federal union, but it wasn’t fiscally federal. The southern states, with wealthier residents, contributed more to the collective Indian revenue pool. In the seventies, under Indira Gandhi’s centrally planned economy, there was virtually no fiscal federalism. The Union government redistributed resources based on need, and the poorer states, with higher fertility rates and therefore higher population and population growth, received a much larger share of the revenue than they generated within the state. The fundamental issue was not about population or people; it was always about money!

The Janata government, elected after the Emergency, undid much of the damage of the Forty-Second Amendment through the Forty-Third and Forty-Fourth Amendments, but didn’t undo the changes to Articles 81, 82, and 170.

The reason the freeze impacted the Lok Sabha, instead of the Rajya Sabha - which is designed as the Council of States - is that budgetary allocations or money bills (per Article 109), are not required to pass the Rajya Sabha. They only need the approval of the Lok Sabha. Thus, a fiscally centralized system only punishes wealthier southern states through a reduction of proportional seats in the Lok Sabha.

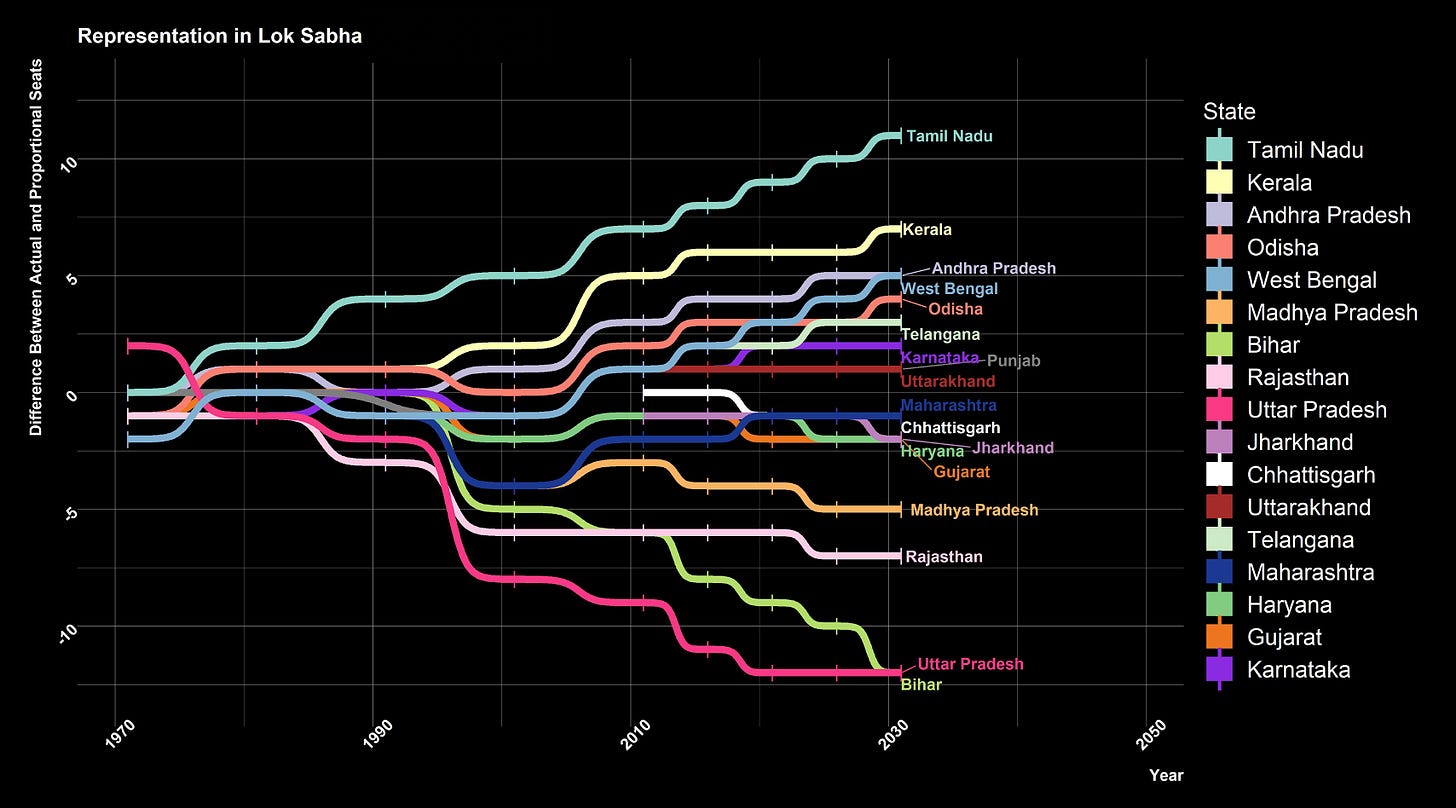

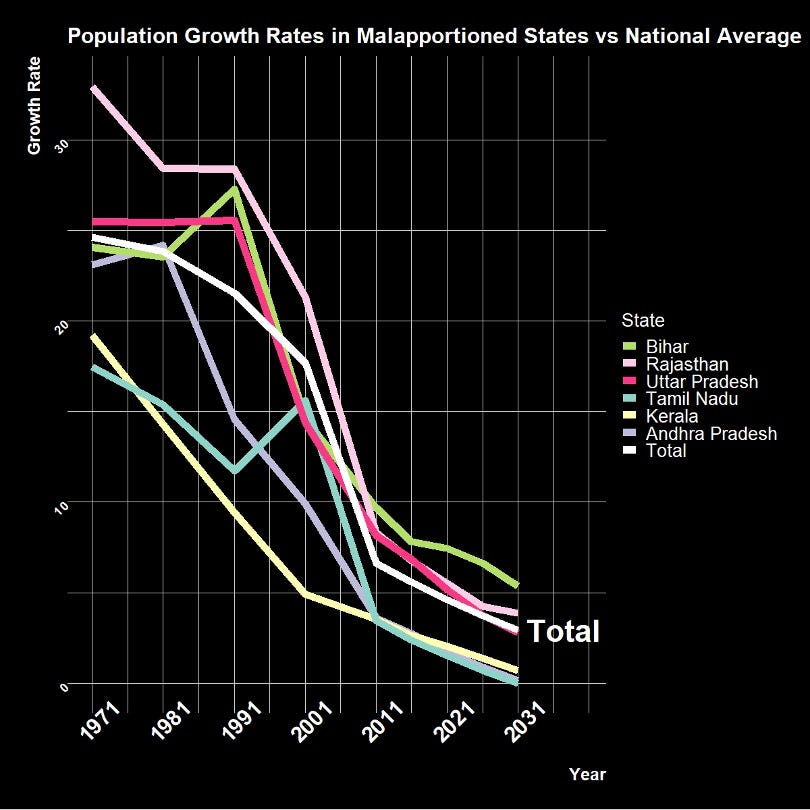

The change in India’s demographics, fiscal centralization, led to malapportionment during the delimitation freeze from 1976 to 2001 (shown in the figure1). By 2001, Tamil Nadu had five seats more than its population share and Uttar Pradesh had eight seats fewer than its population share. As expected, poorer states like Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, and Bihar are disadvantaged and lost seats relative to their population proportion, while Kerala and Andhra Pradesh gained seats. Maharashtra, the recipient of the highest in-migration, often loses a little in seat share despite a decline in fertility rates.

When the time came to revisit the issue in 2001, the Vajpayee government also postponed the decision to 2026 due to the fragile nature of the coalition. This was Vajpayee’s third term as prime minister, with the first term lasting only 16 days in 1996. When the NDA coalition won in 1998, it was with the support of many regional parties including AIADMK, which famously left the coalition in 18 months because of which the Vajpayee-led government fell.

When he returned as prime minister with another NDA coalition in 1999, it was with coalition partners like DMK and Telugu Desam Party, from states that would lose political power in Parliament if the 1971 census freeze was removed. However, there were other issues to consider. First, population growth within states was also uneven. Second, there was a movement to carve out smaller states from Madhya Pradesh and Bihar, an issue BJP had been sympathetic to for years. Also, the malapportionment of SC/STs, who have a constitutionally mandated allotment of parliamentary seats based on the population (Article 330), was a concern. So, the Vajpayee-led arrived at a constitutional compromise.

The Eighty-Fourth Amendment extended the 1971 census freeze on the total number of seats per state in the Lok Sabha/state legislatures until the publication of the census figures after 2026 (which is expected in 2031, unless the 2021 census is delayed so much that it is only published in 2026).

The Delimitation Act 2002, under which the Fourth Delimitation Commission adjusted the number of seats reserved for the scheduled tribes/castes, applied the 1991 census data. Soon after, the Eighty-Seventh Amendment continued the number of seats allotted to each state based on the 1971 census but made an accommodation for redistricting within each state based on the 2001 census.

The consequence was that the constituency size within each state was more symmetric. The new states, Chattisgarh, Uttarakhand, and Jharkhand, were not severely malapportioned as a consequence of the constitutional amendments and within state redistricting policies implemented between 2001-2003.

But every single state in India has a different constituency size, and the sizes, especially for the larger states, are not converging but diverging! This is because the liberalization of the economy since 1991 led to a higher growth rate for all states, but not at the same rate. The southern and western states grew faster, and the drop in fertility rates and difference from the northern states have become even more stark since 2001.

Since the 2021 census numbers are still not available as I write this in July 2023, for most of the graphs in this post, I used census data until 2011. For projections since 2011, I used the 2019 Report of the Technical Group on Population Projections by the National Commission on Population, which provides projections from 2011-2036 for all Indian states and UTs, and was made available in November 2019. I also roughly crosschecked these estimates with Election Commission data (accurate for population over 18), and AADHAAR data. This helps triangulate and come up with better growth estimates. At this point, all scholars projecting malapportionment are working off estimates based on some assumptions, and the differences are not very large given the extent of malapportionment. For instance, malapportionment based on projections from March 2019 are discussed in this paper by Milan Vaishnav and Jamie Hintson.

Today, the asymmetry in seat share for states looks much worse than it did in 2001. Tamil Nadu has nine seats more and Kerala has six seats more than their population proportion. While Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, respectively, have nine seats and twelve seats less than their population proportion.

By 2031, when the delimitation freeze ends, the problem will only intensify. Uttar Pradesh and Bihar will likely fall 12 to 13 seats short of their population proportion, and Tamil Nadu will likely have 11 seats more than its population proportion, with all other states somewhere in between.

Why is the delimitation freeze based on 1971 census numbers a problem?

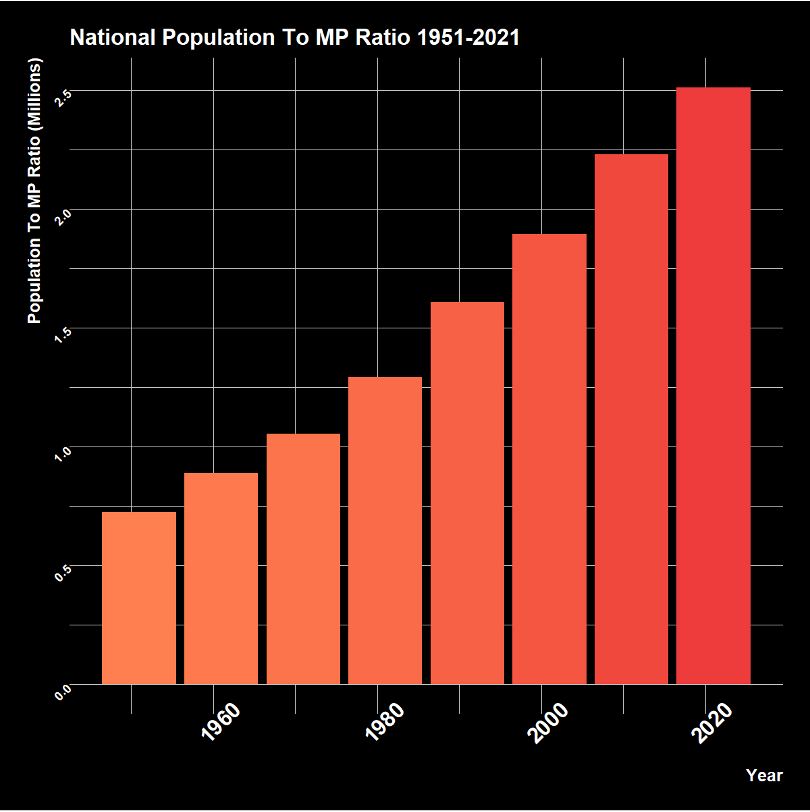

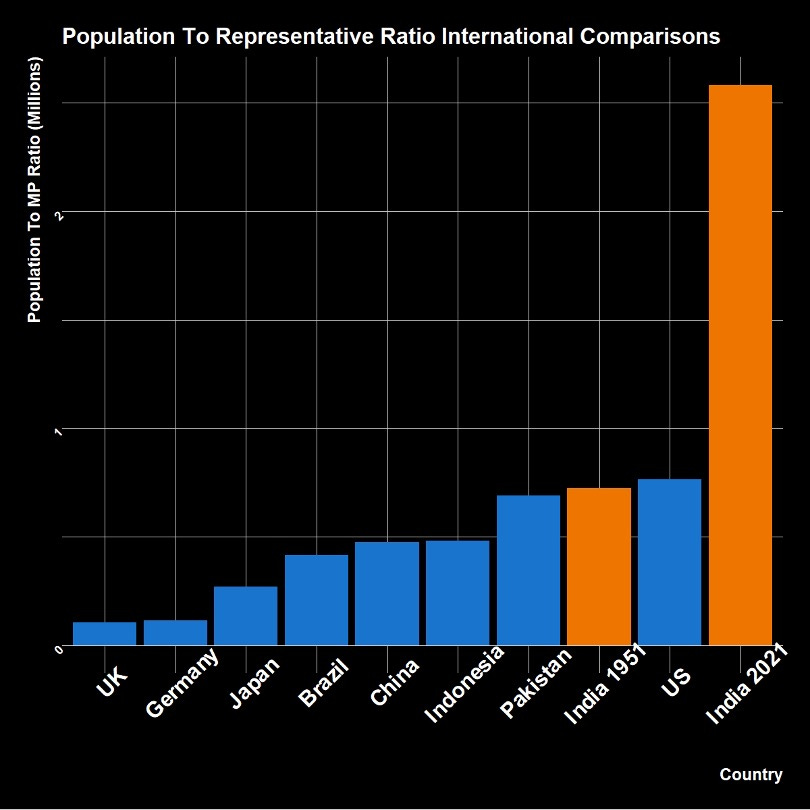

To begin, let’s address a simple issue. There are consequences of freezing the seat share based on census data from half a century ago. First, all Indians are underrepresented (though not equally so) because the Indian constituencies are too large.

Currently, across India, the average MP represents 2.5 million people. The size of each constituency is too large compared to other countries and compared to the original Indian Constitution, which capped the ratio at one MP per 750,000.

The second consequence is that India no longer adheres to the principle of “one person, one vote” in its electoral practice. One aspect of the “one person, one vote” concept, as envisioned by Ambedkar, was about granting every single Indian over 18 the right to vote in elections. India has adopted universal adult franchise since the birth of the republic in 1950. But to give the principle of “one person, one vote” any meaning, constituency sizes must be roughly equal. The random circumstance of being born in Bihar means that the constituency size is about 3.1 million, but if the same person is born in or moves to Kerala, the value of their vote increases because the constituency size is 1.75 million.

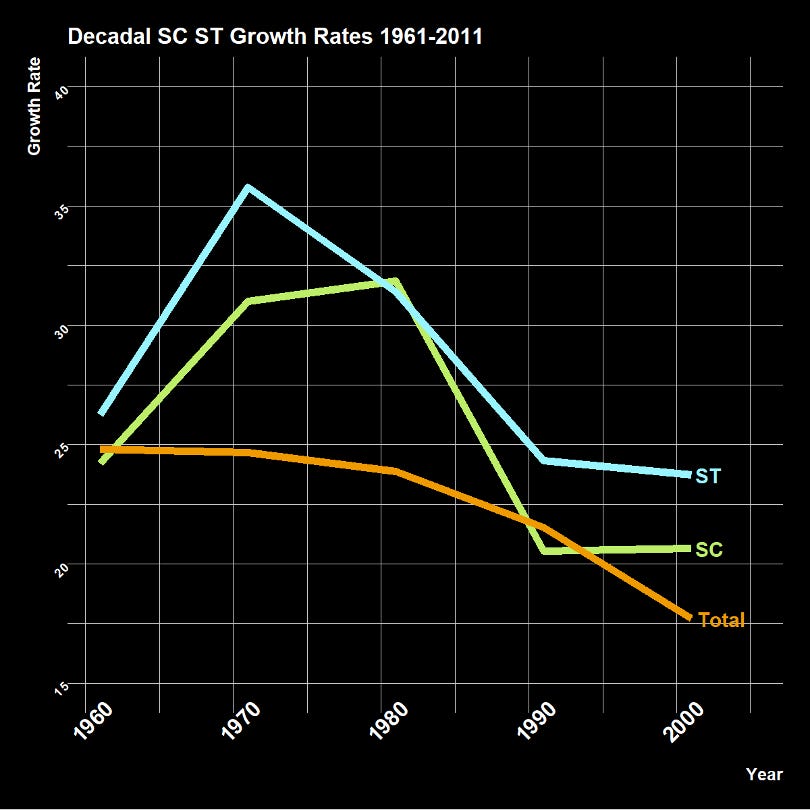

But aside from the principle of “one person, one vote,” other asymmetries exist, and some groups are underrepresented compared to others. Most of these are a result of when fertility rates started declining for a given socio-economic group.

It’s well established that economically prosperous regions have lower fertility rates. The poorer the region, the higher the fertility rates; in a fast-growing developing economy like India, poorer regions experienced a fall in fertility rates later than relatively richer regions.

Consequently, poorer regions are affected more by the 1971 freeze. Poorer Indians are trapped in regions that have higher malapportionment, and therefore, are underrepresented in Parliament.

This also impacts youth adversely. Because regions where fertility rates fell later have more young people. The states with larger average constituency sizes have a larger share of the population below 25. Youth are underrepresented in Parliament, and this problem will only worsen.

We can also identify specific marginalized groups that are more likely to have experienced a decline in fertility rates more recently. SC/ST fertility rates are both higher and dropped later compared to other groups.

The Indian constitution mandates that electoral seats are reserved for SC/ST groups in each state. The number of seats reserved for SC/STs in each state is based on the population share of SC/STs in the given state/UT (Article 330). Since the adjustments made in the Eighty-Fourth and Eighty-Seventh Constitutional amendments and the Delimitation Order of 2008, some of the asymmetry has been reduced. Now, the SC/ST groups are estimated to be 4 seats short in the Lok Sabha, relative to their population in the states.

Another group affected by the delimitation freeze are Muslims, as Muslim fertility rates are higher and declined later than other religious groups. However, Muslims differ from SC/STs in that they are overall a smaller group and do not have any reservation of electoral constituencies in the Lok Sabha.

Hindus are 5.5 times larger in population relative to Muslims. So the slightly higher Muslim fertility rates does not mean that (1) Muslims will electorally or otherwise outnumber Hindus in India, or that (2) only Muslims are impacted by delimitation. Since total number of Hindus are 5.5x Muslims, more Hindus are adversely affected by the malapportionment. But the 1971 freeze, and the kicking the can down the road in 2001 to 2031, means younger Muslims are more likely to be in malapportioned states and therefore underrepresented.

And this underrepresentation or loss of franchise is experienced by all the voters in a given state, and they respond accordingly. Voter turnouts are lower in larger constituencies.

Some possible solutions

To uphold the principle of “one person, one vote,” India needs to correctly apportion its constituencies and ideally increase the total number of constituencies across all states. If the Indian Parliament doesn’t postpone dealing with the issue again, the problem will require a permanent and incentive aligned solution in 2031.

One option is to return to the original constitutional ratio of one MP per 750,000, in which case the Lok Sabha would need to expand to 1,872 seats. In my view, this would be ideal for an MP to function as a real representative with manageable constituency sizes. It would also reduce the power of the executive, as transaction costs of coordination increase in the Lok Sabha, and the legislature is governed using more overlapping caucuses.

If that seems excessive, another version of achieving this has been suggested by Vaishnav and Hinston, where the total number of seats in the Lok Sabha increases such that no state loses it’s current number of electoral seats. To achieve this without malapportionment, the total number of seats in Lok Sabha would need to be 848 by 2026. However, it’s important to note that the states would lose proportional share/power in Lok Sabha based on the change in demographics since 1971.

The problem is not just one of uneven population growth across states. That alone does not lead to these problems, especially given the Indian constitutional design where even the upper house, or Rajya Sabha, allows for apportionment with population growth.

The issue arises from our peculiar bicameral design for states (easy to create and alter state lines under Article 3) and India’s fiscal centralization. The Indian fiscal system is designed such that states’ collective share in total revenue is less than 40%, and the states’ total expenditure is about 60%. The remainder is raised and spent by the Union government.

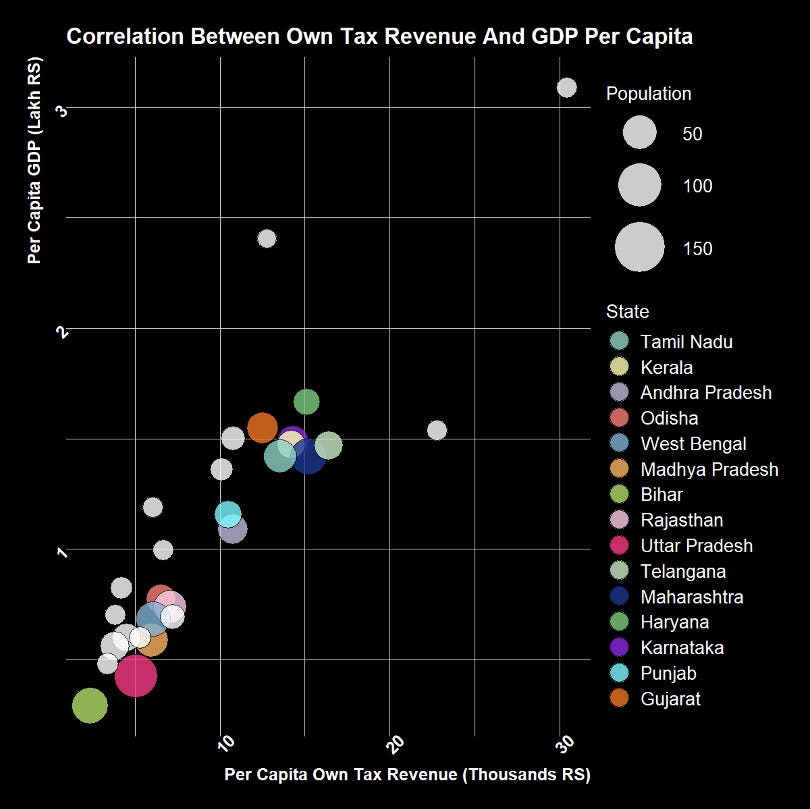

The Indian system operates primarily through intergovernmental transfers managed by the Union government. Some states spend more than they raise, while other states spend less than the proportion raised. There’s considerable variation among the states on their fiscal dependence on the Union government, largely based on the variation in states’ gross domestic product (GSDP) per capita.

Per capita revenues raised by the states are highly correlated with per capita GSDP. Based on 2014-15 revenue and expenditures, M. Govind Rao has calculated the correlation coefficient at 0.940. For instance, Kerala’s own state per capita revenue is seven times Bihar’s. And per capita expenditures of the states, even after accounting for intergovernmental transfers, are correlated to GSDP per capita. Rao estimates the correlation between developmental expenditures (expenditures on social and economic services) and total expenditures to per capita GSDP at 0.786 and 0.614 respectively.

Even after intergovernmental transfers from the Union government, low-income states spend less than high-income states. But high-income states don’t enjoy all the revenue that is raised off the income and productivity of those states.

Solution 1: Fiscal Federalism + Perfect Apportionment of Seats

The simplest way to resolve the problem without any other constitutional changes is for India to move to a system of perfect apportionment, based on the most recent census. Simultaneously, through the Finance Commission, India could move toward a completely decentralized/devolved fiscal system.

Each state would have hard budget constraints, greater revenue-raising capacity, and keep most or all of its revenue, without a central pool disbursed based on development needs. The Union government would levy and spend only Union taxes, and reduce its expenditure to the Union government domain, not involving itself with state-level schemes or development expenditures. Although not as drastic as what I’ve suggested, Pranay Kotasthane has proposed moving towards a 60-40 split in revenue sharing in favor of the states.

Although this solution is the most sensible in the long run, it’s both economically and politically unviable in the short run (i.e. by 2031). The main issue with moving away from intergovernmental transfers is that states aren’t converging in their economic outcomes. They’re diverging.

The poorer states won’t be able to commit much to development expenditure through revenue raised by the state. Nor can they build revenue-raising capacity very swiftly. Therefore, a fiscally decentralized system would rely more on migration pull through economic productivity of the southern states, which isn’t simple because of linguistic fractionalization and NIMBY attitudes.

It’s also politically unviable in the short run because it requires the political actors at the Union government level to reduce their control over total revenue, and instead hand over fiscal control to the state level actors. Every politician’s power is based on the size of their spending power/budget, and while this could be done by gradually changing the Union-State shares over time, it is difficult to revamp the revenue sharing swiftly (before 2031, which is when the delimitation freeze will be revisited).

Solution 2: Intergovernmental Transfers With a Senate-Style Rajya Sabha

A second possibility is to maintain intergovernmental transfers but create a U.S. Senate-style Rajya Sabha, where each state gets the same number of Rajya Sabha seats irrespective of population, to counterbalance the population-proportioned seats in the Lok Sabha. Nitin Pai has recommended this system where each state, regardless of size, has the same number of Rajya Sabha seats. This idea has been seconded by Pranay Kotasthane. This has also been suggested as one possible solution by Vaishnav and Hinston.

This approach requires some amendments to the constitution, most importantly to Article 3 (governing the creation and alteration of states) and Article 109 governing money bills. This solution won’t resolve the problem unless money bills must pass in the reimagined Rajya Sabha. It also requires amending the Representation of People’s Act to mandate that Rajya Sabha members are domiciled in the state they represent. Otherwise, the party in power at the Union government could abuse Rajya Sabha membership to achieve its political ends.

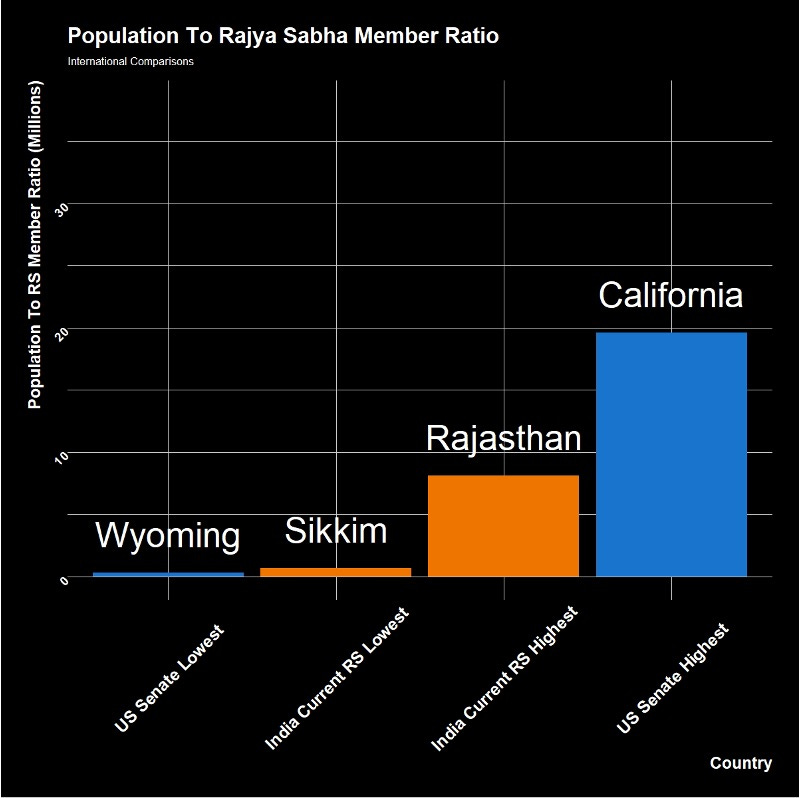

The problem is that while it resolves the malapportionment in the Lok Sabha, it introduces a more severe version of it in the Rajya Sabha!

For instance, India’s current malapportionment in the Rajya Sabha due to the 1971 census freeze is not as severe as the malapportionment in the U.S. Senate.

If we implement a U.S. Senate-style Rajya Sabha, the malapportionment in the Rajya Sabha will be even more severe than in the US.

Solution 3: Revenue Sabha + Perfect Apportionment of Lok Sabha Seats

A Reimagination of India’s Bicameral Federal Union

A third way to resolve the problem while allowing for intergovernmental transfers to help poor states develop, and simultaneously avoid severe malapportionment in the Rajya Sabha is to redesign it completely based on fiscal principles. Here I present a radical idea of converting Rajya Sabha into Revenue Sabha to compliment a perfectly apportioned Lok Sabha based on the 2031 census.

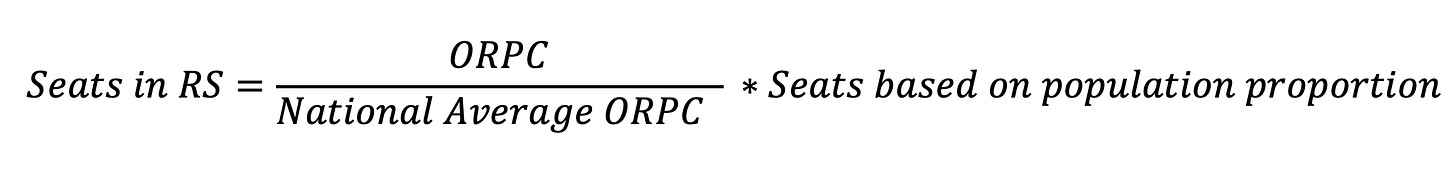

I recommend using population proportions based on the most recent census for Lok Sabha seats. But my suggested change is to allot the seats in the Rajya Sabha based on revenue-raising capacity, using States’ Own Revenue Per Capita (ORPC) as the benchmark.

I suggest the following formula for allocating seats for each state in the Rajya Sabha, reimagined as Revenue Sabha:

The reason I use ORPC for each state is that it does not include revenue that is collected in a particular state which doesn’t accrue in that state. For instance, a lot of firms are headquartered in Mumbai or Bangalore, but the corporation/corporate tax is based on the activities of the firm across the country.

This has two benefits. First, each state has very strong incentives to build revenue-raising capacity, which is highly (almost perfectly) correlated with state GDP per capita. This would align political incentives with economic growth, because the only way of increasing political power in the Rajya Sabha is by pursuing economic growth.

Second, it is very difficult to game or misrepresent own revenue per capita, or increase and manipulate it to gain political power in the short run.

Here are some examples of how this works. I used the pre-pandemic actuals (not budget estimates) for ORPC for Bihar, which was Rs. 2,356 compared to the national average across all states of Rs. 8,771. The ratio of Bihar’s ORPC to the national average is 0.27. At present, Bihar has 16 seats in the Rajya Sabha. If we use current population proportions for the Rajya Sabha, Bihar would have 21 seats. But in the Revenue Sabha, Bihar would receive seats based on its revenue-raising capacity per capita, as well as population proportion, bringing the seat share to 5.6 (if we choose to round up, then 6 seats, and if we round down then 5 seats).

Similarly, for Karnataka, ORPC is Rs.14,323, which is 1.63 times the national average ORPC. Karnataka has 12 seats in Rajya Sabha, which will come down to 11 if Rajya Sabha were perfectly apportioned by population share. But in the Revenue Sabha, Karnataka would have 19 seats (rounding up).

If we calculate the number of Rajya Sabha and Revenue Sabha seats for all states, the picture looks like this:

In this system, it is not about north versus south, or a particular language, or region. Just like Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh; Haryana, Gujarat, Uttarakhand etc. will gain because they are richer and have a higher ORPC than the national average. And Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Jharkhand, and Assam will lose seat share because they have not developed their economy and revenue-raising capacity.

This will not require some amendments I had suggested in the previous solution. For instance, Article 3 (how states are created, altered etc.) can stay as is, since splitting of states, or combining small states will lead to a calculation of the ORPC as a ratio of the national average to determine Rajya Sabha seat share.

The Revenue Sabha will require amending Article 109, which governs money bills. This system will not resolve the problem unless money bills have to pass in the newly designed Rajya Sabha/Revenue Sabha.

The domicile (or lack thereof) problem in Rajya Sabha can still become a serious design issue though representation is based on fiscal interests, which cannot be easily manipulated, but some members not representing the states’ interest can be brought to the Rajya Sabha. So ideally, the Representation of People’s Act should be appropriately amended.

A perfectly apportioned Lok Sabha, based on the 2031 census, along with a Revenue Sabha will create the right political incentives for a plural, developing economy like India. Even with aging demographics, shifting and changing internal migrations, etc., many decades from now, when Kerala ages and is no longer as productive, and Bihar develops as a young and vibrant economy, the Revenue Sabha will automatically accommodate that. At that point, Bihar may have to transfer both manpower and revenue to Kerala. India can continue to have a system where fiscal resources are shared and political power is not malapportioned across states.

Shoutout to

for his help with some of these data visualizations and Shreyas Narla for his research assistance for the working papers on which the podcast, my 2022 lecture, and this post are based.

I really love ur substacks, u r the best indian substacker

Wow! This was excellent. It explains the history, why we are where we are clearly. It also brings out the negative consequences of not updating the MP count, and how the problem of addressing constiuent needs are aggravated is even further by not updating MP counts.

The possible solutions are clear, yet list the challenges that each has.

Excellent post!