Kamala Harris, Usha Vance, and the twice-born thrice-selected Indian American elite

They didn't fall out of a coconut tree.

It’s only been a couple of days since Biden stepped down and endorsed Kamala Harris. I’ve lost count of the “first Black/Indian American/Asian American female president” emails and ads flooding my inbox. Just last week, I learned that JD Vance was Trump’s running mate when I got a dozen messages asking about the Telugu-speaking Kamma caste. And no, these weren’t from the extended family WhatsApp group gossiping about a cousin. Most messages were from Americans trying to understand the buzz around JD Vance’s wife, Usha Vance (née Chilukuri), an American born to Telugu-speaking Indian immigrants.

That buzz around Indian Americans in politics only intensified with Vivek Ramaswamy’s speech at the Republican National Convention (RNC) and Nikki Haley following the party line to endorse Trump. With Kamala Harris at the top of the Democratic ticket, Indian Americans are making waves on both sides of the political aisle, and everyone’s taking notice.

Indian Americans, though just 1.5% of the U.S. population, have an outsized impact. They’re not only the highest-earning ethnic group but also occupy top positions at Microsoft, Google, IBM, Adobe, and FedEx. They dominate the field in STEM and medicine, and now, they’re stepping into the political spotlight on both sides of the aisle.

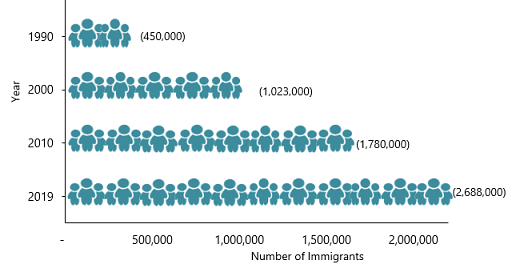

The 1980 census reported only 206,000 Indian immigrants in the US. Kamala, Usha, Nikki, and Vivek’s parents belong to this cohort of immigrants.

How did the children of Indian immigrants reach the top of US establishments in just one generation? Should we view them as part of the elite or categorize them as BIPOC — Black, Indigenous, and People of Color? Are they more likely to vote – or now, increasingly run – as Democrats or Republicans? And what does all this mean for the broader political landscape and policies on immigration, race, and DEI?

I answer all these questions by explaining (1) the composition of Indian Americans in the US, especially from the lens of caste; (2) the origins of when and how Indian Americans came to the US; (3) the political leanings and views of the more recent Indian immigrants on immigration reform and DEI as a relatively small minority in the US.

Twice-Born and the Thrice-Selected

When Biden endorsed Kamala Harris, the NY Post, predictably, dubbed Harris the first D.E.I. President, with Charles Gasparino arguing that Harris’s rise was because of race, not merit. Equally predictably, NYT’s Lydia Polgreen fired back, claiming, “If Kamala Harris Is a D.E.I. Candidate, So Is JD Vance.” Her point? “Race isn’t the only diversity,” and elite colleges like Yale also court white guys from tough backgrounds, like Vance. Polgreen thinks the reason only Harris gets called out is “written on their faces.”

But I’d say it’s written in Harris’s elite family background and caste.

Harris’s mother, Shyamala Gopalan, was born to PV Gopalan and Rajam and raised in a Tamilian Brahmin family in India. This background likely afforded the Gopalans status akin to white privilege in Indian society. And because of the Brahmanical advantage, families like Shyamala’s, Vivek’s, and Usha’s often boast multiple generations of college graduates in a country still striving for universal literacy and numeracy. Shyamala and all her siblings were encouraged to pursue advanced graduate degrees typical of Tamil Brahmin families.

What set Shyamala apart was her decision to move to the US for graduate work at Berkeley, a rare choice for Indians at the time. At 19, while studying for her PhD, she became actively involved in the civil rights movement, through which she met Donald J. Harris. Donald, now professor emeritus and the first Black economist granted tenure at Stanford University, has his own notable background. Born to a landowning family in Jamaica, he was raised by his grandmothers – one a descendant of plantation and slave owners, the other a farmer and educator. In 1950s Jamaica, where formal schooling was a privilege enjoyed by merely 10% of children, Donald attended Titchfield High School, originally established in 1786 for the education of white children from poorer backgrounds, because there was no system in place for the education of the children of slaves. He went on to the University College of West Indies, then UC Berkeley.

Compared to her parents’ elite academic careers, Harris’s degrees from Howard University and University of California, Hastings College of the Law seem par for the course. Or as Zarna Garg, would say, within the Indian community she is “a bit of a disappointment…because she is not a doctor.”

So why has Harris become a DEI punchline with the right and defended as a legitimate DEI star with the left? It is partly because most of the commentary misses the elite backgrounds of many Indian immigrants to the US. These aren’t your typical “tired, poor, huddled masses.” We’re talking about India’s educated upper crust.

In their excellent book “The Other One Percent: Indians in America,” Sanjoy Chakravorty, Devesh Kapur, and Nirvikar Singh [hereinafter CKS] argue that Indian Americans succeed because they are thrice-selected.

Most Indians in the US come from upper or dominant castes. The millennia-long practice of marriage endogamy and selection gave individuals and families from these castes a multi-generational advantage in access to education. Second, they were selected through highly competitive exams in India to enter top educational institutions or by the American schools where they studied. Ponnavolu writes, “Indian Institutes of Technology (IITs) accept only one in 50 applicants. (For perspective, Harvard takes one in 19, and Oxford, one in six.” Third, US immigration policies favored skilled professionals, creating a filter for the best candidates, further refined by the competitive American job market with the H1B visa lottery since the mid-nineties. These selection processes ensure that Indian immigrants often arrive as top performers with strong educational and professional backgrounds.

Ironically, JD Vance understands this better than his progressive counterparts. He married Usha Chilukuri, born in San Diego, to Indian-born Telugu-speaking professors. Her father, Krish Chilukuri, is an aerospace engineer from the prestigious IIT Madras. His father, Chilukuri Ramasastry, was a member of IIT’s founding faculty and the best student prize in physics memorialized in his name. Usha’s mother, Lakshmi, is a marine biologist and now provost at one of the colleges in UC San Diego. Usha’s great aunt Shanthamma Chilukuri, now 96, continues her career as a physics professor in Visakhapatnam.

It doesn’t surprise me, or most Indian Americans, that Usha Vance went to Yale and got her master’s at Cambridge University, followed by a law degree at Yale. She served as a law clerk to the then District of Columbia Circuit Judge Brett Kavanaugh and for Supreme Court Chief Justice John Roberts.

Like Usha, Vivek Ramaswamy also went to Harvard and then Yale. J.D. Vance met Usha at Yale Law School, while Vivek met his wife Apoorva during her time at Yale Medical School. Vivek’s parents are from the Tamilian Brahmin Iyer community. His father V. Ganapathy Ramaswamy, worked as an engineer and patent attorney for General Electric, and his mother, Geetha, is a geriatric psychiatrist.

Usha Vance’s credentials only seem puzzling to those who have no clue about the early Indian immigrants to the US. My progressive American friends view her as BIPOC, which means she is, by definition, disenfranchised and received a hobbled start in life. While Indian Americans are people of color, to the extent that they are not Caucasian or white, treating them as BIPOC entirely misses the point.

Usha’s last name is typically associated with the Telugu Kamma caste. But she and her family are vegetarians and, as one friend said, “sound” like Telugu Brahmins. Various message boards and Twitter litigated her family’s origin story. While caste doesn’t matter in American politics, Indians and Indian Americans (often inadvertently) view Usha’s life and career through this lens.

Americans often miss the importance of caste when understanding India and Indians. The Indian caste system is a complex social structure with thousands of subcastes, or jatis, linked to geographic regions and linguistic subgroups. These jatis fall under four main varnas: Brahmin, Kshatriya, Vaishya, and Shudra, and Dalits [the self-identification term used by erstwhile outcaste/untouchable groups]. Non-Hindu groups like Muslims, Buddhists, Sikhs, and Christians, while outside the traditional Hindu structure, have their own hierarchies and unofficial relationships to the varnas and jatis.

Unlike race, caste markers are invisible to those outside the system, hidden in plain sight for Indians who can discern it from someone’s last name, region, dialect, pronunciation, and even diet. Moreover, most Indians that Americans meet in the US are from upper or dominant castes, obscuring the real impact of the caste system. But, make no mistake, caste intricacies shape social interactions, opportunities, and identities in India, and the Indian diaspora abroad. In 2020, Cisco was the first US based company to be sued for caste based discrimination. The California legislature passed Senate Bill (SB) No. 403 to include caste as a protected category. Not just caste discrimination, but also Gandhian civil disobedience made its way to the US, as South Asian Dalit activists went on a hunger strike to persuade Governor Newsom to sign it into law. Newsom vetoed the bill in October 2023.

To most Americans, whether Vance is Brahmin or Kamma seems like a petty difference between an East Coast elite with degrees from Yale and Princeton versus a West Coast elite with degrees from Stanford and Berkeley. But to Indian Americans, especially Telugu-speaking, and Indians back home, it still matters significantly.

Both Brahmins and Kammas are dominant and privileged groups from Telugu-speaking communities in Andhra Pradesh. The development of colonial Western education and the need for an English-fluent bureaucratic class allowed Brahmins to dominate various fields. In the Telugu-speaking area [now split into two states, Andhra Pradesh and Telangana], non-Brahmin castes include Kshatriyas, Arya-Vaisyas, Kammas, Reddys, Kapus, Balijas, Veļamas, and Other Backward Classes.

Kammas and Reddys are landowning communities, but Kamma property is concentrated in the fertile Krishna and Godavari deltas, while Reddys own land in the arid Deccan plateau. Consequently, Kammas started out as more prosperous, paving their way to upward mobility in academic fields, while Reddys have dominated the state’s political power since Independence. This changed in the 1980s when N.T. Rama Rao, the first Kamma Chief Minister of Andhra Pradesh, came to power, followed by his son-in-law Chandrababu Naidu.

Kammas are known for their propensity to migrate for investment opportunities, including to the United States. The Telugu film industry, also the origin of RRR and the Oscar-winning foot-tapping earworm Naatu Naatu, is dominated by the Kammas. Kammas are prominent in the Telugu diaspora, controlling the Telugu Association of North America (TANA). In response, Reddys created the American Telugu Association (ATA), demonstrating that caste rivalry persists even in the US.

Usha Vance’s family appears to be Brahmin, a group more easily recognized by Americans as elite and privileged. Their surprise at Usha’s stellar resume exposes the lack of education and context about India. The right is surprised because she is the daughter of immigrants, while the left views Usha as BIPOC and J.D. Vance as someone with “white privilege.”

It will become easier for the left and the right to place the various Indian Americans on the political stage this year once they learn a little more about the kinds of Indian subgroups that emigrated to the US.

The Three Phases of Indian Immigration

Indian immigration to the US in the nineteenth century was in very small numbers, mainly sailors. From 1900-1965, only a few thousand Indian-born or Indian-origin people were in the US. In the early part of the twentieth century, American immigration policy was quite literally racist; with inclusions and exclusions based on race. In the early twentieth century, following the backlash against Indian immigrants in Canada, Indians in the US termed Hindus, were clubbed together with the movement against allowing Asian immigrants.

The 1917 Immigration Act banned admission with the purpose of settlement, created the “Asiatic Barred Zone” which prohibited immigrants from most of Asia including all of British India, and was followed by the 1924 Immigration Act, after which even Indians outside the Asiatic Barred Zone were barred because they could not be naturalized. A small group of Sikh Punjabis entered the US, first legally, and then illegally through Mexico. Eventually, the subgroup was large enough to have another subgroup of children of Punjabi Sikhs married to Mexican Christians in California.

While this was not a ban against students visiting American Universities, both the social movement against Indians and the immigration restrictions incentivized few to come to the US, think Indian constitution framer B.R. Ambedkar, and other anti colonial agitators like Lala Lajpat Rai and Jaya Prakash Narayan who visited the US as young students. The absence of a preexisting Indian network did not help matters. The effective ban continued for almost half a century, and it was only with the 1965 immigration reform act that the doors opened to immigrants without specific regard to their race.

Normally, when this kind of immigration reform occurs, the host country signals an openness to accept immigrants. But the sending countries don’t respond uniformly. Depending on the political and social structure, often the poor and disenfranchised find their way to a new country. Others, like Cubans, may even get pushed out by their political system and leave because they have nothing to lose. The Indian case was interesting. In the sixties, the poor and disenfranchised Indians did not have the resources to make the trip to the US only to find jobs in agriculture, restaurant kitchens, or in construction. But the elites, armed with high levels of education conducted in English, and social and financial capital, could afford to move to the US, and access the incredible jobs in STEM, medicine, and academia.

CKS classify Indian immigration to the US into three phases - the Early Movers from 1965-79; the Family Reunification from 1980-1994; and the IT Boom from 1995 onwards.

The Early movers under the liberalized regime (1965-1979) were accomplished individuals who gained legal entry based on their education and skills. CKS write that forty-five percent already possessed or later acquired graduate or professional degrees, especially in medicine and STEM.

Normally one would not expect the elites from the sending country to respond to this kind of change. But the political system in India granted universal adult franchise in 1950, which informed a new political mobilization among the non-elites. That, combined with various affirmative action programs, and a stagnant socialist economy, reduced the relative status and opportunities for the elites, incentivizing them to look for greener pastures. Thanks to their elite status inherited from a colonial period, they spoke English, were not the first in their families to attend an elite university and could easily assimilate with Americans. And with the American promise of religious freedom, the largely upper-caste immigrants could hold on to their religion and culture and assimilate in every other way.

Most of the current generation of Indian Americans in politics are children of this generation of early movers.

Like Nikki Haley’s parents, Ajit Singh and Raj Kaur Randhawa. Ajit got his Ph.D. at the University of British Columbia. He was a biology professor at Voorhees College, and Raj got a master’s in education and started a career as a South Carolina public school teacher.

A few years before the Randhawas, an aspiring engineer Amar Jindal fell in love with a classmate’s sister, Raj (née Gupta), a doctoral physics candidate in Chandigarh, Punjab. They sold Raj’s dowry jewelry to travel to the US when a pregnant Raj received a scholarship offering her a spot at Louisiana State University. A few months after moving, Piyush “Bobby” Jindal, eventually the 55th Governor of Louisiana, was born in Baton Rouge.

Like Harris’s mother Shyamala Gopalan, others were brought in through the university system. Vinod Khosla, now considered old Silicon Valley royalty, moved to the US to pursue graduate degrees at Carnegie Mellon University and Stanford after his engineering degree at India’s prestigious IIT. Khoslas are from Punjab’s dominant ‘Khatri’ castes and have been elite martial and trading castes depending on the region and century. Vinod, born to this family, selected first through the very competitive IIT examination, then the US university selection system, and finally the American labor market, is a near-perfect example of the first movers from 1965-1980.

The second big immigration move came from 1980-1994, along the lines of Family Unification. The demographic that moved in this wave was also largely dominant castes but less likely to be selected through the American university system. Think of the classic Indian American owned motels dotting all of small-town America. Twenty-five years ago, Tunku Varadarajan reported that “slightly more than 50 percent of all motels in the United States are now owned by people of Indian origin.”

However, going deeper, Varadarajan found dominance of one community, “about 70 percent of all Indian motel owners -- or a third of all motel owners in America -- are called Patel, a surname that indicates they are members of a Gujarati Hindu subcaste” of Patidars. He charmingly dubbed their group’s success the “Patel Motel Cartel.” Twenty-five years have passed, and now Indian Americans are said to nearly dominate the sector. The family-based immigration allowed entry of newcomers, and the caste-based networks traced back to multiple generations in India allowed the new entrants to raise scarce capital and collateral for down payments on motels.

Gujaratis were the largest immigrant subgroup in the 1965-79 immigration rush, which set them up to bring in family members after 1980. Another group that benefited from the family reunification immigrant wave was the Punjabis, who had even older family roots in the US.

The third group, CKS track, are the tech workers from India who moved to the US since the mid-nineties. The nineties saw a new IT-driven boom in the US, and with it came a fresh generation of Indian immigrants. These were mostly Indian-trained engineers and STEM students, lured by the success of earlier generations of Indians. The US tech job market was on fire, and employment and skill-related visas again became the hottest tickets to entry. In this wave, South Indians, primarily Telugu and Tamil speakers, dominated. Unlike the early movers, who were medical doctors and PhDs, this most recent immigrant wave mostly had master’s degrees and quickly found their place in the job market. They were still a highly educated group, with about a third of them already holding or later earning master’s degrees. Still, they had fewer numbers with professional and doctorate degrees that defined the Early Movers generation. CKS write,

“So specialized was this group of immigrants that by 2013, the India-born made up well over 10 percent of the American labor force in some fields (like computer science and engineering, and electrical engineering and technology). These new arrivals—the IT Generation—entered the United States along two major paths: as students in science and technology fields with F-1 visas or as workers in computer-related professions with H-1B or L-1 visas; and their corresponding status for immediate family members (spouse and children), the H-4 and L-2 visas. We estimate that 90 percent or more of all Indians stayed on in the United States and became permanent residents (by getting green cards) or citizens. This new immigration stream was enabled by adaptations to U.S. immigration policies (most notably the H-1B visa program, and more briefly, the L-1 visa program) and higher education policies in India (most notably the burgeoning of private engineering colleges).”

Are Indian Americans Republican or Democrat?

Almost every survey shows that Indian Americans have consistently leaned Democratic in recent years. The 2020 Carnegie Endowment survey found 56% identified as Democrats, with 72% planning to vote for Biden in the presidential election. The 2022-23 Pew survey showed that 68% of Indian American voters leaned Democratic. NPR’s 2020 analysis found that 77% voted for Clinton in 2016 versus 16% for Trump.

The survey results are not surprising. Indian Americans are a small minority in the US, especially in religious terms. The 2020 Carnegie Endowment finds that Indian Americans perceive the Republican party as intolerant of minorities and overly influenced by Christian evangelicalism. The Republican stance on immigration, including legal immigrants, is also a factor. Those who identify as Republicans are primarily moved to do so because of economic policy, healthcare, and illegal immigration.

Immigration

Seven out of 10 Indian immigrants to the US moved after 2000. The pathway is often through the American education system, where 1 in 5 of all international students in the US are Indian-born, second only to Chinese students. Indians are more likely to stay and benefit firms in the US. H1B visas are for highly skilled foreign workers, and nearly three-quarters of H1B visa beneficiaries are Indian, with Chinese at 12% and Canadians at 1%.

However, one major problem with the US immigration system is that it is punitive towards those who are highly skilled, entered the country legally, and happen to be Indian. It’s not the kind of racist immigration policy from the 1920s, but it is still capped by country of birth. Many H1B visa holders apply for employment-based green cards to gain permanent residency. However, the US imposes a 7% per-country cap on employment-based green cards, disproportionately affecting countries with large populations like India. The annual limit on employment-based green cards is set at 140,000, which includes dependents. The demand far exceeds this cap due to the high number of skilled workers from India, particularly in STEM fields. About 1.1 million of the nearly 1.8 million cases in the backlog are from India (63 percent). Another 250,000 are from China (14 percent).

The pathway from these employment-based visas to a green card is classified into different stages (EB1, EB2, EB3, EB4). Think of it as a line the highly skilled immigrants join, and the wait time depends on the length of each line. David J. Bier at Cato writes,

“For new applicants from India, the backlog for the EB‑2 and EB‑3 categories (which are combined because applicants can move between them) is effectively a life sentence: 134 years. About 424,000 employment-based applicants will die waiting, and over 90 percent of them will be Indians. Given that Indians are currently half of all new employer-sponsored applicants, roughly half of all newly sponsored immigrants will die before they receive a green card.”

The reliance on H1B visas to bring in high-skilled Indian workers to the US exacerbates the issue. H1B visa holders must continually renew their visas to maintain legal status while waiting for their green cards. This creates uncertainty and instability, as any denial of renewal can result in job loss and forced departure from the US. Indians are typically married and have families, and they have one of the lowest divorce rates of any group. As the H1B to green card wait continues endlessly, their spouses, typically highly skilled, cannot work on their H4 dependent visa.

The “aging out” issue for children of H1B workers in the US is creating significant challenges for many Indian families. When these children turn 21, they’re no longer considered dependents and lose their spot on their parent’s H1B visa or green card application. They must then initiate their own visa or green card process, essentially starting over. This situation can disrupt their education, as they may lose their legal status to remain in the country while studying, potentially forcing them to return to India even if they spent their entire life in the US through legal entry.

The US Citizenship Act (HR 1177) 2021 proposed changes to the US immigration system. It aimed to eliminate the per-country cap on employment-based green cards. It sought to increase the annual limit on employment-based green cards from 140,000 to 170,000. It also planned to recapture unused visas from previous years. These changes could have reduced the backlog for the 1.2 million Indians in waiting. The act offered exemptions from numerical limits for STEM Ph.D. holders. For Indian immigrants, the reforms meant potential reductions in wait times and improvements in job mobility. The bill included provisions to prevent children from “aging out” of dependent status. Because of the Republican opposition to HR 1177 and the 60-vote filibuster threshold in the Senate, the law did not move in Congress, leaving millions of Indians waiting.

The Republican party, including high-profile Indian Americans like Vivek Ramaswamy, repeatedly postures that they are against illegal immigration but support legal immigration for high-skilled workers. However, when the opportunity came in 2021, Republicans did not come through for legal Indian immigrants. Because of this, Indian Americans are likely to remain on the Democratic side.

While both U.S.-born and naturalized Indian Americans favor the Democratic Party, this tilt more pronounced for U.S.-born Indian Americans. This Democratic preference is likely to strengthen as each year, approximately 150,000 Indian Americans become newly eligible to vote—a third through naturalization and the rest children of immigrants reaching voting age.

DEI

The country “quotas” holding Indians back add insult to other real and perceived injuries. Not all, but many highly skilled Indians in the US have already experienced a different quota system in India. Affirmative action, or reservations and quotas as they are called in India, are based on caste. As members of privileged and dominant castes in India, they often moved to the US because this kind of affirmative action does not apply, and the perception of Americans allowing the meritorious to rise persists. However, elite colleges having quotas limiting Asians and South Asians in favor of other BIPOCs creates tension.

These issues have persisted for over a decade, with over 60 Asian American groups coming together to address it. In its 2023 opinion Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. President and Fellows of Harvard College, the Supreme Court found that Harvard’s admissions program considered the race of applicants in a way that was not narrowly tailored to achieve the educational benefits of diversity and disadvantaged Asian American applicants. For instance, “an African American [student] in [the fourth lowest academic] decile has a higher chance of admission (12.8%) than an Asian American in the *top* decile (12.7%).”

Elite colleges limiting Asian and South Asian admissions in favor of other BIPOC groups and elite high schools like Thomas Jefferson High School for Science and Technology changing their admissions exam requirements to foster diversity have left Indian Americans feeling aggrieved and angry for being punished for what they see as their children pursuing excellence.

Another example is student debt forgiveness for students from elite families, while Indian parents judiciously saved for decades to pay for their children’s college tuition. These policies have left Indian Americans feeling alienated by some policies most closely associated with Democrats.

When Biden was still in the race, the Asian American Voter Survey 2024 noted a decline in Biden’s support from 65% in 2020 to 46%, while Trump’s support only grew from 28% to 29%. These surveys indicate a strong but potentially shifting preference among Indian American voters, and Kamala has an opportunity to consolidate that vote in favor fo the democrats. But her Indian American identity will only go so far, this group will care about policy issues like healthcare, DEI and immigration.

On these issues, the Indian American support is for the Democrats to lose rather than for the Republicans to win.

Identity matters, but the question is whether the political class understands that it matters to provide context or just for its own sake. To use Shyamala’s refrain, you think Indian Americans fell out of a coconut tree? As Harris says, “You exist in the context of all in which you live and what came before you.”

Good overview of Indians and Indian-Americans for Americans.

One quibble though. You mention the Cisco case, which was certainly the first of its kind. But you don't mention that the suit was dismissed and in fact, the California Civil Rights Department was penalized by the courts for pursuing the case because it was meritless.

https://www.thehindu.com/news/international/us-court-penalises-california-state-department-in-caste-discrimination-lawsuit/article68310663.ece

In my view, the case is better understood as Americans trying to fit the idea of caste into their familiar domestic categories and failing rather badly at it. For some of the same reasons as you go through in the article.

The ‘caste’ background laid out paints a picture with a broad brush - painting communities with a single stroke when a few enjoyed privilege. This leads to incorrect perception for other people of same communities.

Also, the article smells of author’s bias to me.